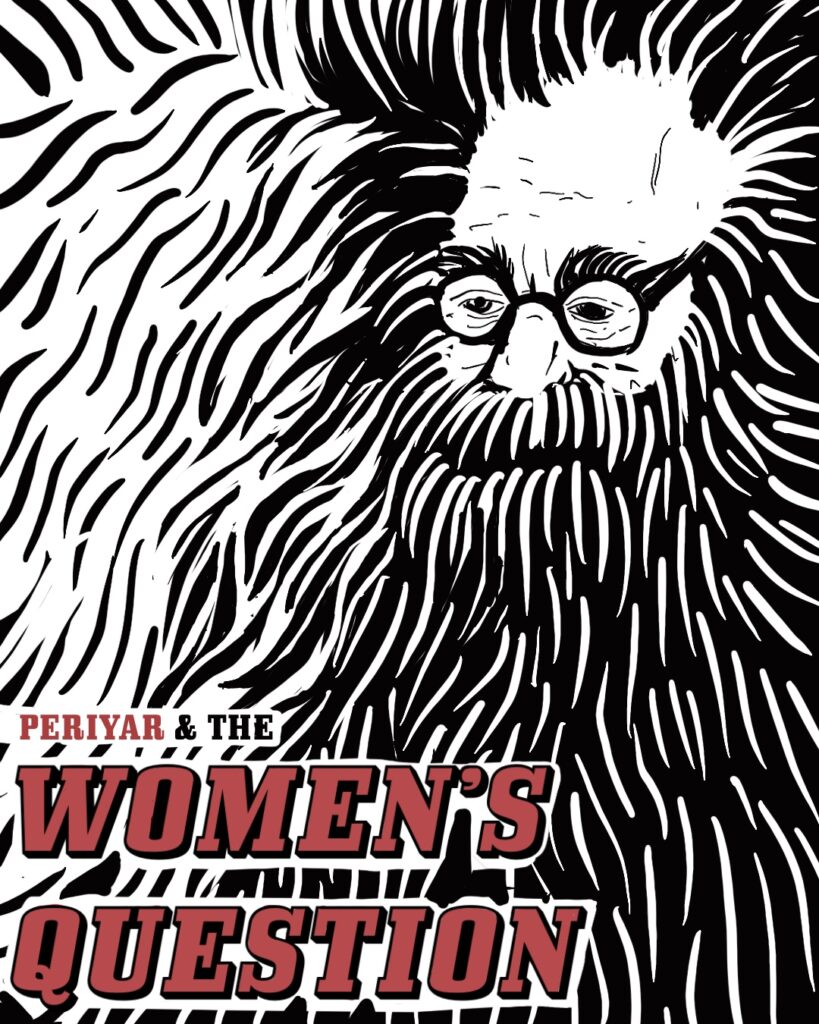

Thanthai Periyar’s revolutionary ideas forged the path for building the self-consciousness to attain equal freedoms and paved an equitable discourse towards social justice.

Illustration by Ajinkya Dekhane

Thanthai Periyar was a crusader, far ahead of his time. He fundamentally believed that India would not attain full freedom without women and the untouchable castes attaining freedom and equal rights. His work for the liberation of the oppressed classes left an indelible mark on the lives of people and of generations of reformist movements to come.

Periyar argued that the downtrodden classes needed to understand the true meaning of liberty themselves. Any reliance on others to give them their rightful freedoms was meaningless. In his words, “to hand over the responsibility of (the) depressed people’s freedom and welfare to us is equivalent to handing over the goats to the butcher, and not otherwise.”

In order to enhance the freedom of women, he insisted on the equal right to hereditary property, educational training, economic independence, and the right to contraception.

In the 1920s, Periyar became acutely conscious of the need for inclusion of women in politics and social reform – not as mere subordinates, but as fellow revolutionaries. In the Vaikom agitations, he encouraged the mass participation of women, and his wife Nagammai played an important role in the agitations too. He expressed that his peers in the Congress party and the Justice Party did not give adequate importance to the women’s question and seldom, sought to sideline it. To Periyar, however, women’s liberation was a key to ending oppression in society. In the Chengalpet Self-Respect conference held in February 1929, Periyar and the Self-Respecters passed resolutions demanding equal rights of property for women, widow remarriage, abolition of child marriage, freedom to choose spouses defying caste and community norms, besides encouraging women to enter professions of their choice. These resolutions rattled not just the Congress, but also many in the Justice Party.

Women Enslaved constitutes what can be called Periyar’s ‘early writings’, and is comprised of ten essays he wrote on the women’s question between 1926 and 1931.

These essays were compiled and published as a booklet in 1934, perhaps the first work of Periyar to be published in a book form, under the title ‘Pen Yen Adimaiyaanal.’

In his preface to a 1942 reprint, Periyar wrote that the aim of the booklet was to “demonstrate the different factors by which women were enslaved and continue to be so enslaved, and also the different ways and means by which they could emancipate themselves and live as free people”, adding that this booklet was written for both men and women and for “people of all religions, societies and nations.”

Periyar’s views on women’s liberation were centuries ahead of the prevailing time. He saw the oppression of women operating in dual ways; one economic, which deemed them as unpaid labourers at home and thrust upon with the burden of housework including the bearing and rearing of children; the other cultural, the moral codes of Brahminism, which legitimised their oppression, glorified it, and made them complicit in it. He said that for 3000 years, the oppression of women went unchallenged because “men thought it right to give respect and pay obeisance to Brahminism.”

Periyar proceeded to attack the idea of ‘love’ as has been traditionally understood. Notably, ideal forms of love were greatly eulogised in ancient Sangam Tamil poetry. For instance, the Ainkurunuru, an anthology compiled roughly in the second to third centuries AD, consists of five hundred poems dedicated exclusively to love. What is significant about this poetry is that it is located in the secular, where gods rarely figure at all. Again, while such poetry was celebrated by the Tamil nationalists, Periyar dismissed them for providing rigid, essentialist notions of the genders. Periyar revolted against the ancient, and he found the ancient revolting. He believed ancient notions of love and undying commitments had no place in a rational, modern society.

He calls out such advocates of love to be “ignorant of general natural dispositions”. He believed that biological callings and the freedom to choose should be criteria for partnership, not culture or pressures from family or society. He argues that the idealisation of love or the family relationship would force couples to live in “perennial dissatisfaction and harassment.” Instead of idealising love, Periyar sought to view it in a utilitarian way, as a private emotion that should contribute to the wellness and pleasure of individuals and not a norm imposed by society that compels people to remain bonded in unjust relationships. Periyar opposed the idea that “people’s expressions of love and desire must be brought within certain discipline and they ought to be expressed between particular individuals, in a particular way only.

Thanthai Periyar’s revolutionary ideas forged the path for building the self-consciousness to attain equal freedoms and paved an equitable discourse towards social justice. Periyar’s efforts towards the emancipation of the oppressed classes were far beyond his times and continue to live on through his legacy even today.