As a ‘first generation’ Dalit, I tried to share my confusion about my ‘Dalit-hood’ with fellow ‘assertive’ anti-caste people but it was counterintuitive. They could not process why a person born in a Dalit family should be asking if she is ‘Dalit-enough’

Illustration by Ajinkya Dekhane

Confession versus Assertion

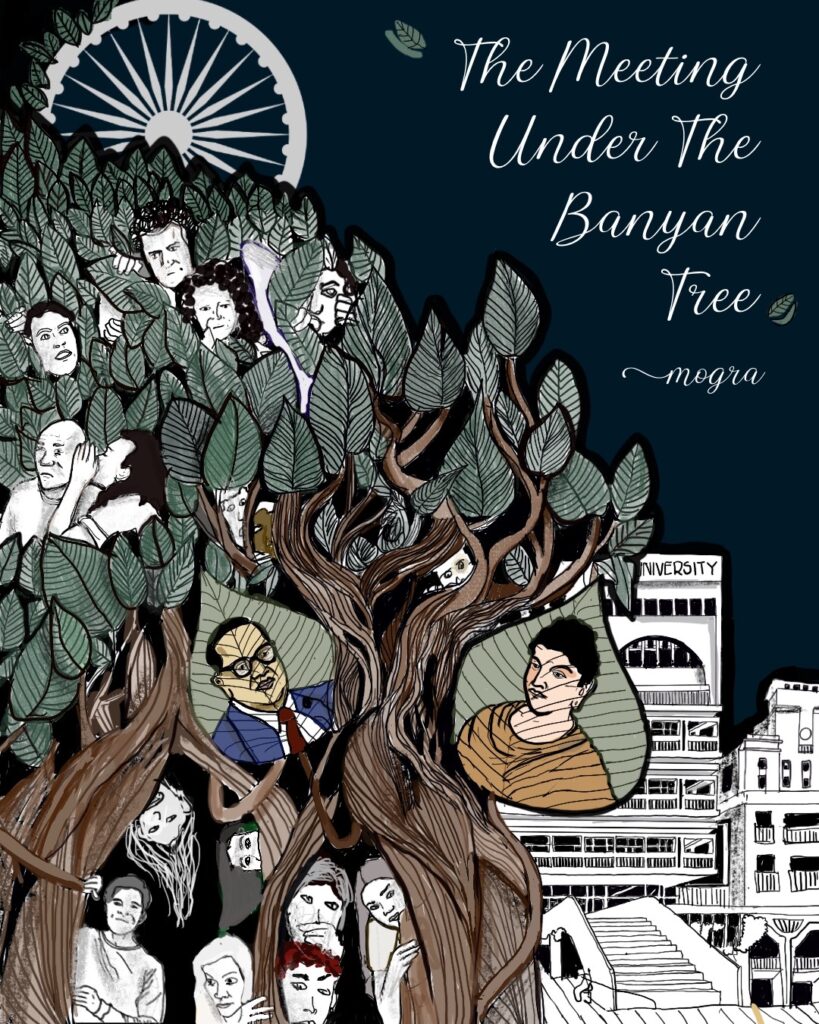

The inaugural meeting of our anti-caste collective in the university was held in January. It was a cold, breezy evening but I wore sandals (instead of socks and shoes) since my feet were wet from the bath I had just taken. We were supposed to assemble under the banyan tree and when I reached, a sparse crowd had already gathered. My friend – a tiny shape sandwiched between two tall people – waved at me. As soon as I was within her reach, she held my arm and asked me to walk around with her to invite the bystanders, to ensure a larger audience.

The university we studied in, like most other universities, had its faculty and top-position holders mainly consisting of people from historically privileged castes and classes. The university did not have a Cell for support of Scheduled Caste (SC) students; the Ambedkar memorial lectures were primarily led by non-SC scholars, and there was yet no Ambedkar Chair (to foster research on and around various forms of marginalisation among other sociological and anthropological discussions). In part, this is what the meeting under the banyan tree was meant to address – to find ways of forming solidarity and kinship among the historically marginalised people despite the lack of structural support.

Soon I realized even if I want to forget where I come from, people and systems around me wouldn’t let me do that. My desire, mobility as well as aspirations—everything is shaped by my queerness and caste. I grew up with many people telling me life is easy because we have reservation and that’s the only way of imagining a career because otherwise we aren’t good enough. I had many people reminding me to stick to what ‘my people’ do— manual-labor work. I had people warn me my queerness wouldn’t be tolerated in workplace, I must act ‘normal’.

As first-generation learners, as people who were walking into the organized working spaces for the first time, many of us eventually realized how our wish to distance ourselves from our identities comes with the risk of decontextualizing who we are and where we come from. With masking and some mobility through education as we enter UC cis-het dominated spaces, often people tend to look at us in a vacuum without our lived history and reality. They assume if we are sharing space with them, we are equally privileged. There’s comfort in imagining homogeneity that excuses them from reflections of power and privilege. All of us can’t mask or might not want to.

In part, this is what the meeting under the banyan tree was meant to address – to find ways of forming solidarity and kinship among the historically marginalised people despite the lack of structural support.

My friend led the meeting and started with the introductions: she asked everyone to mention their caste. The idea was to highlight something that otherwise worked discreetly (though some people ended up not mentioning their caste, so it was not a compulsion) and turned out there was a good number of people who used the word ‘savarna’ with empty eyes looking squarely at people around them. After my friend’s turn, the buck was in my court. I looked at my toes protruding from my sandals; the tarmac and the gravel; I rubbed my foot against the ground as if removing stuck chewing gum from the sole then muttered with a put-on smile on my face, “Dalit… whatever that means,” and everyone giggled. I could not articulate it then but what I felt at that moment was shame and vulnerability as if I was ousting myself. From what I remember, my friend and I were the only two people who mentioned ‘Dalit’.

Unlike my friend, I was not well-versed with anti-caste political sensibilities. I was born in a ‘lower caste’ family, which had an ‘SC Certificate’ but we were not ‘Dalit’ or ‘Ambedkarite’; what we lacked was a political anti-caste consciousness, and the knowledge and awareness of an unjust structural system. However, it all changed for me when one evening my friend (who led the meeting) came to my hostel room and I saw her contorted face as she made me aware of the suicide of a doctorate student at a Hyderabad university. Since childhood, I had read about caste atrocities but they never felt personal; I was culturally trained to feel like they were ‘natural’, a part of the social order, like road accidents.

But when I looked at my friend, the death of the scholar felt personal; I felt connected to a larger community at the receiving end of a brutal system; as if, if I was not careful, someday, it could be me.

I won’t be a rare case of a ‘lower caste’ person whose parents (mostly the father who is a first-generation government employee) helped raise their children in a protective environment, providing (usually locally available) ‘modern English education’ in an urban/suburban city while keeping away the political and social reality of caste discrimination at bay, to the point that it lent itself as an external experience that only seemed to happen to ‘others’; that if I faced the shame while writing my caste publicly on a college form, it had nothing to do with the larger system at hand but was an individual experience not meant to be spoken out loud.

Even then it was strange and disturbing to say out loud and associate with the word ‘Dalit’ in the meeting, which I had done for the first time. I probably did it to feel connected to people of ‘my kind’; people who spoke out about caste shame and stigma. However, the experience eventually became a disturbing one when later at night I asked my friend what the word ‘savarna’ meant and I realised it was not another variation for ‘lower caste’ but referred to the privileged and dominant castes. At that moment, I realised that unlike myself, there were people in this world who never felt shame while mentioning their caste in public. I was shocked to have witnessed it, which also led to a prolonged spell of depression. I felt I had exposed myself in front of people who were benefitting from the system, people whose community members had made me feel inferior and second-grade in life. It felt like I had unknowingly confessed to a crime among people who were the actual criminals and had made a fool of myself.

A simple resolution would have been to read more about the caste system but for the life of me, I could not.

It continues to feel like the more I will read about it, the more I will know about myself, and having spent over two decades in ‘Sanskritised ignorance’ and as a ‘first-generation Dalit woman’ with no immediate support system, I’m not sure I can ‘safely’ claim my historical identity while not compromising my life and career. What would I do with all the awareness if I can’t find a community or a family to share it with? What does an individual do with awareness if it’s not communal? This sense of insecurity comes from caste- and gender-based vulnerabilities.

As a girl, having been constantly invalidated and scrutinised, I have been rewarded to stay quiet, not make a sound or be angry. I am supposed to take care of the chores and not question anything because that is not required of a daughter-in-law or a wife. Whenever I cook well, the moment is celebrated but not once are my academic and career achievements highlighted and validated. Invisibilisation started pretty early. All these experiences contribute to the fact that I struggle with figuring out who I really am; and if I am rewarded to be an ignorant woman, what would being an aware Dalit imply in that context? It’s a conundrum I’ve not yet figured how to live with.

When I did come across Dr Ambedkar as an anti-caste political and social scientist (more than just the guy who wrote the constitution as I was taught in school) and other anti-caste thinkers and concepts, I could contextualise the shame I had internalised since childhood. I felt seen and heard intellectually. Yet, emotionally, I felt unseen and unheard. It is ironic that I was looking for a specific articulation to validate my feelings of non-specific, multiple identities-based confusion. Franz Fanon’s concept of ‘double consciousness’ and Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of ‘intersectionality’ remains the closest articulation of how I feel being a Dalit woman. Half a decade later, I continue to hound for moments of clarity so I feel less of a sub-specie.

Intergenerational, Gendered ‘Identity Crisis’ and Psychotherapy

As a ‘first generation’ Dalit, I tried to share my confusion about my ‘Dalit-hood’ with fellow ‘assertive’ anti-caste people but it was counterintuitive. They could not process why a person born in a Dalit family should be asking if she is ‘Dalit-enough’; for most of them, it was a misplaced, unnecessary thought not worthy of sensitive discussion. People who would understand my experience, people who had to live a dual life like myself, of having to ‘pass’ as a savarna while dealing with internalised caste shame and trauma were off the radar for obvious reasons.

As a community member, I needed specific support and I could not get it because even as ‘insiders’, we tend to homogenise what it means to be ‘Dalit’.

It took a couple of years to finally be able to put my feelings of confusion in context. One evening, I put the abovementioned doubts in front of scholars of queer literature and they told me about ‘survivor’s guilt’ in the context of the Holocaust; the notion of feeling guilty for not being poor enough, downtrodden enough, thoroughly abused and dejected enough, feeling ‘less Dalit’ in a certain context, among specific people ought to be a savarna manifestation, which, unfortunately, some people even in the Dalit community tend to subscribe to. As a community, we need to find a healthy, compassionate language to address our individual experiences without jeopardising or invalidating each other.

After the meeting in January, I also faced the full impact of realising what it means to be a ‘Dalit woman’, especially, after having lived more than two decades believing I was only a woman. Everything that was preached about feminism during undergraduation, fell flat without explaining how patriarchy functioned hand-in-glove with caste supremacy; one may also call this ‘savarna feminism’. The introduction to feminism made me hate the men in my family. It took years of assessment and self-work to comprehend how the men in my family are not individuals to be hated upon but to process the system that they replicate in order to maintain their social standing; that controlling women’s sexuality and mobility is predominantly a Brahminical idea that has contaminated many minority and marginal cultures.

Understanding this does not make it easy for me to live through everyday life but it helps to channelise my energy in the direction that call matters.

I have been in and out of depression since my early teenage years and have been in therapy since undergraduation. Studying in a metropolitan city helped; I cannot imagine going for therapy while living with family members who are disconnected from their emotional, sensitive side just to be able to remain functional. However, in the seven-eight years of being in therapy, I had never mentioned what it meant to come from a ‘lower caste’. In the last couple of years when I did mention the Dalit doctoral scholar’s suicide in Hyderabad in therapy, which was heavily covered by the national media (though more because of the incident’s ripples in another university in Delhi), the therapist blatantly shook her head, claiming no knowledge of the event – an event that had turned my world upside down. How does a therapy patient, in such a cultural scenario, convince herself of her relevance to the therapist who does not bother knowing about anything beyond their immediate (probably privileged) context?

In fact, recently, when the Hathras incident happened, I found myself to be vulnerable in a society that did not resolve to care for women who come from marginalised castes and identities. When I shared this feeling of vulnerability with another therapist and highlighted how the non-Dalit identity of the therapist was only worsening my feeling of being exposed, all she came up with was a patronising statement: ‘I am not the enemy’.

Soon after this instance, she abruptly ended the sessions without bothering herself with giving me a referral so I can continue therapy with another therapist (which has a technical term called ‘abandonment’ and is unethical). Even bringing the oversight of the therapist to her seniors (from non-Dalit privileged backgrounds) did not yield any result. They shrugged their shoulders when I asked them for Dalit therapists. These are the same people who have taught MA, MPhil, and PhD Psychology students for decades and yet make no efforts to enquire how their SC students have fared after college and if anyone among them is actually a practising psychologist or a psychiatrist whom they can refer to patients later on. They are blissfully unaware as long as students, privileged like themselves, continue to get licenses and patients.

What remains outrageous is when they are made aware of the lapse, their go-to penance scheme is to suggest workshops and researches on ‘the Dalit (and Muslim) experience’. Indian psychologists and psychiatrists are yet to bother themselves with non-mainstream, marginalised patients without coming to us like we are exotic specimens to be analysed.

The meeting under the banyan tree was not just a random, casual gathering for me.

It initiated an important journey of questioning my socialisation, realising that living with ‘ignorance’ and ‘awareness’ are both politically complex forms of existing for a Dalit/SC person (especially, women, gender non-conforming folks) and neither can be conveniently picked over the other; not when one comes from a historically compromised identity where both systemic visibility and invisibility can relay a toxic chain reaction

Author’s Note: No part of this memoir may be produced, reproduced, or published in any form, for any reason, without the explicit permission of the author (to be sought via the Mavelinadu Foundation).

Mogra

This author has chosen to remain anonymous.