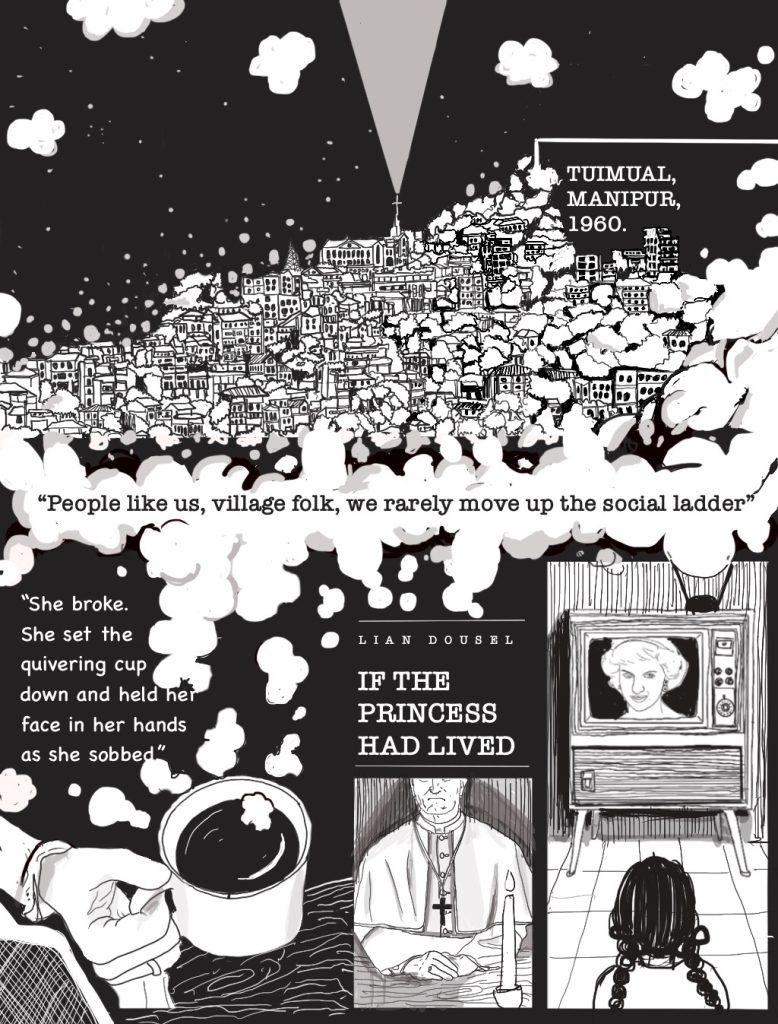

There had been rumours spreading through the village in the last couple of days, and finally, there it was—an actual television set.

Illustration by Ajinkya Dekhane

My mother’s attention was glued to the television screen on July 29, 1981. She was sixteen then, and the people who knew her would say she was as beautiful as the Princess of Wales, and then I’d think, but how much more tragic?

Few people had television sets back then. They barely had electricity. Tuimual wasn’t unlike other villages on the southern hills of Manipur—proselytized by colonial Christian missionaries, enlightenment and culturalization brought unto them in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a trade—for every new refinement that arrived, old customs had to die to make room; for the establishment of hospitals and schools, churches had to be built. The powers that be had brought God and industry to a land where once rain and sun were deities, and where once barbarism existed, now were people of faith and community.

Balance was an elusive state to be in, especially after the departure of the missionaries. The old ways and the new struggled to coexist in harmony, for the principles inherent in those ways juxtaposed each other in more ways than one, and in that struggle, the promised industry, the anticipated modernity fell to the wayside and remained in neglect for a long time. Electricity did finally arrive in Tuimual in the early-1960s, although in infrequent spurts, and the first radio was bought by the village chief sometime in the early ’70s. Folks from every household would gather at the chief’s house at odd hours to listen to the radio, listening to the happenings around the world, mesmerized not by the news itself but the idea of ant-sized people crowded inside that small black box delivering strange words—even those who had gone to school and could decipher the English alphabet had trouble comprehending words like ‘Apollo 13’, ‘Munich’, or ‘Saigon’. They were simply content with the notion that they could listen about those parts of the world that they would never get to see.

Then, one evening in 1980, the village chief came home pulling his trolley rickshaw with a giant cardboard box standing in the bed. Children and adult alike came out of their homes, curiosity and giddy excitement taking hold of them all, to spectate this new marvel, brought all the way from Lamka town. There had been rumours spreading through the village in the last couple of days, and finally, there it was—an actual television set. My mother had been one of the first to hear the bell on the rickshaw and the first to abandon her chore and rush out to catch a glimpse of the box that held the future inside.

Illustration by Ajinkya Dekhane

“Do you remember the last time you saw my mother,” I asked her, “before she . . .?”

“I do,” she said as she took a deep breath, as if to remind herself to stay in the present—or bothered by the reminder. But her smile returned as she went on. “She just had you. We hadn’t seen each other much after she got married in ’86. We were all envious of her at the time. People like us, village folk, we rarely move up the social ladder, especially not back then. Lamka, for us, was as unreachable as those cities you see on TV, and to have that chance to live down there, to start all over again, to have a family . . . to be able to give our children what we couldn’t have . . . to dream about it was all any of us could do. If any one of us was going to have that chance, then it was your mother. Have I told you how beautiful she was? It came as no surprise when she got that chance, having stolen the eyes of . . . your father. By all appearances, he was a good hardworking Christian man who added great value to the church and the community, and being the headmaster of a children’s home gave him a good reputation. Nobody cared that he was almost two decades older and married once already; he had the means to provide, and that was all that mattered. We all thought it was foolish of your mother to even hesitate at all. She wanted to continue studying, having a job or a career or something or the other, but realistically, it was impossible for women like us to get out of this dearth that we were born into unless we married our way out of it. Of course, your mother eventually gave in. How could she not have, with the way everyone, including me, hounded her, pressured her, acted like it would be some kind of betrayal if she didn’t accept the proposal? We knew so little. We were so young.

“And so, she was married,” she said with a nostalgic smile. She turned to the window and watched a butterfly flutter in, her eyes following its movements until it finally found its way out again. The silence stretched, but I waited. Almost a minute later, she turned her attention back to me. “We all assumed she was happy, and there was no reason to believe otherwise. No concrete reason, that is. Whatever . . . disturbance that was brewing inside her . . . she hid it well. It couldn’t have been easy, to say the least, especially after she lost her first two, but every time we saw her, there was never a hint of that latent illness. She was still that same girl sitting in front of the TV, mesmerized by the fairytales on screen, although more mature and maybe a little more subdued, but she was still her. And when she had you . . . Oh, let me tell you. That was a fairytale on its own. It seemed like just about every single person from Lamka and Tuimual dropped in with gifts to congratulate her, to catch a glimpse of you.

“I couldn’t make it to the naming ceremony because I had . . . domestic problems of my own, but I dropped in a week later. We hadn’t seen each other in over a year. You know how life takes us in different directions . . . And it was nobody’s fault. No, not at all. We just . . . drifted apart. We weren’t kids anymore. We were wives, with duties. I wish we’d been closer, but it was out of our hands. Anyway, I was conscious of the distance that had grown between us, and of the fact that I never showed up after her second . . . loss, but she greeted me warmly when I finally came around, as if I’d been by her side through it all. I felt extremely guilty, but she simply brushed it all away. That was your mother.

“I spent the day with her, taking care of the baby—you, so sweet—and there was nothing, absolutely nothing that even hinted at what was to happen in the years to come.”

The memories I had of my mother were no more than flashes, like the light of the sun though the thick roof of the woods in the breeze, always momentary, the wind never strong enough to part the branches so enough light shone on the damp and dark undergrowth I often found myself in. I would lie on the mossy floor with my head resting on snaky roots, looking up at the underside of the leaves above. Sometimes it rained, and the drops would fall thick and slow. Sometimes it rained while the sun still shone, and the drops would glitter as they fell, like fairy dusts for a moment, with all its infinite atomic life within, before, inevitably, they would hit the ground and disappear, like they never existed at all. And what light that shone through between those tiny spaces would hurt my eyes if I didn’t look away. I’d been looking away for all twenty-nine years of my life, taking refuge under those broad leaves betwixt the roots at the base of the trunk, safe from the storm, hidden from the light.

“When did you first hear about it?” I asked.

“They were nothing but rumours at first. You must remember, it’s not uncommon now, and certainly not uncommon back then to hear stories of domestic abuse, of wife-beatings. Sadly, it was not any less normal than anything else that went on anywhere, and there was very little anyone could do about it, or even anyone would do about it. It really was rarer to find a husband who’s never laid a hand on their wife at least once. I’ve had my fair share too, but I was luckier than most, and I was stronger than most. See now, your father, he was a . . . disciplinarian, as you no doubt know, and he was a proud man. On top of that, he had certain views on certain things that even now makes me shudder. To hear people say it, the real spiral began after the second loss. A miscarriage is never easy to move past, but by all appearances, your mother recovered quickly enough, physically and mentally. But the stillbirth of the second was a burden too heavy. It hurt your father’s pride greatly. He felt insulted, he felt emasculated, and so he . . . acted out, without subtlety and without a care. To him, your mother’s purpose was to bear him children and nothing more, and she failed at that.”

The sun came out again, and in the rays, she found the distraction she needed to pause. A moment later, she called her daughter-in-law into the room and asked her to make tea. At the sound of the stove clicking on, she continued, “Everyone thought things would be on the mend when she had you, and for a time it looked like they were on the mend. But then, there eventually came those rumours. Those ugly rumours. It’s impossible to even imagine that a mother could ever willingly hurt their own child, barely a year old. It was preposterous. I refused to believe it. I thought it was just some . . . cruel and malicious accusation by your father to hurt your mother. I never put it past him. And you know how people like to make mountains out of molehills. Maybe your mother accidentally bumped your head on the doorframe, maybe your father didn’t like the way she held you; who’s to say? But the rumours did not go away, not completely. It was lying dormant, waiting for the next one to pile onto.

“You just turned . . . three, I think,” she went on with a sigh, glancing towards the kitchen. “A broken arm. Again, of course, I didn’t believe it. Maybe it was a sprain, maybe just a knock. It was just so impossible to even imagine it. And even when I learned the truth, I still couldn’t believe it. I didn’t want to. I knew her. I grew up with her. You know? There had to be some logical explanation . . . something, even if it was far-fetched, that could somehow make sense of it all.”

She paused again as her daughter-in-law, a few years younger than me, brought in two cups of tea on a tray and set it down on the table. She took a cup, even though it was still too hot, and brought it up to her lips and gently blew. “I have a theory,” she then said. “I have done an endless and unhealthy amount thinking about it all, sometimes staying up half the night. It doesn’t change anything, not one bit, or even remotely succeeded in soothing the horror I still feel about it sometimes, but . . . You see, your father, like I said, was a proud, traditional man. Too proud, and too traditional, if you ask me. After the two losses, you, a boy, were a godsend. Ah, his prayers were answered. God listened to him,” she said those words very slowly and very clearly. “He was possessive and protective. He took complete ownership of you, and your mother, to him, became nothing more than a source of nourishment, an unfortunate necessity. And for your mother . . . after losing two babies and to have the third effectively taken from her, her motherhood made to mean nothing, instead of love, resentment grew. She knew that every trace of her would be smothered away by your father and there would be nothing she could do about it. You were an extension of him. She couldn’t hurt your father, couldn’t stand up to him, but you were defenceless, so she did the only thing she thought she could do to hurt him.”

She tried to take a sip of the tea, but it was still too hot, so she set it down on the arm of her chair and crossed her hands on her lap. “To be clear, that is just my mind trying to make sense of it all. But, regardless of whether that’s true or not, or if the truth was something much stranger or much simpler, it was painfully clear that your mother was troubled. Her mind was troubled. Deeply.”

A smile waxed across her face as she asked, “Do you know the significance of your birthday?”

“February 11?” I asked.

Her smile did not fade as she said, “The princess was in India on that day. Your mother always believed it was a blessing, a vital, prophetic element to your health . . . to your survival.”

“I was five when the Princess died. Do you know how my mother was then?”

Her smile waned. She reached for her cup again, and I did the same as well. “I only saw her again about a week after the news. I hadn’t seen her, probably in over a year. She was . . . already half gone by that time. I couldn’t say if she knew about the death. If she did, she made no mention. I remember, you were in school that day when I visited. I stayed for most of the day. In the morning, she was fresh and clear, far from that raving woman in those stories and gossips that travelled all that way up the hill to us. We talked about . . . normal things, everyday life. You know? We had time to reminisce about the past, about our school days. But we made no mention of the death of the princess. I suspected that she might not have known, or that she knew but was dealing with it in her own way—if there was anything to deal with, that is—and I was afraid that if I brought it up, it might provoke her. Anyway, she seemed clear that morning. She moved about like a proper, diligent housewife. If people saw her then, they wouldn’t believe she could be mad at all.”

She sighed. “But in the afternoon, she was . . .”

She took a sip of her tea, and so did I. It has cooled just enough to not burn your tongue.

“I just don’t understand how a mind can be so utterly lost,” she went on with a shake of her head and staring at the floor beneath her feet. “I was sitting in the living room with her. Then, she went into the kitchen, out of sight just for a moment, and when she returned, she had no idea who I was. She thought I was . . .” she paused. Her face contorted, the composure she had betrayed finally, even if only momentarily. She took a deep breath and continued. “She thought I was a . . . a reporter, after her, trying to expose her life for the world to see. A reporter? We barely had a newspaper back then. And the more I tried to convince her, the more she was convinced that I was someone else, that I meant to do her harm. It never got better from there. She never got better.”

Illustration by Ajinkya Dekhane

“Did you see her often, after that?” I asked.

She took another sip of her tea before she answered, “No. No, I . . . I couldn’t bear it. I saw her just once more, before she took her own life. She was . . . tethered, to keep her from wandering, from walking out into the streets and hurting herself or others. I tried . . . I tried to talk to her . . . and, I tried to . . .”

She broke. She set the quivering cup down and held her face in her hands as she sobbed. Outside, the breeze rustled the leaves on the trees, and the sun, leisurely in its descent, was bright and unobstructed. There were birds, chirping out of sight, and the sound of a distant hammering drifted in with the wind. Hammerings and drillings and sawing could be heard year-round. This hill, upon which long ago a village was built, now stood proud with a flourishing town on its shoulders. The bricks were stacked higher and higher and every passing year, concrete structures grew taller than the trees surrounding them. The once promised industry, it seemed, was finally arriving.

The house seemed to be caught halfway between the old and the new. The kitchen and the bathroom were tiled, and steel framed the windows beneath the flat concrete roof, while the wooden floor of the living room gapped with age and rusted hinges clung onto the window shutters. The popping and ticking of the tin roof under the sun reverberated in the silence as the woman sitting with me composed herself. She wiped her cheeks with her shawl and picked up her tea again, this time not putting it down until the cup was empty.

A minute after she took the last sip, she spoke again. “It was the times we lived in as well, I would say” she said. “Today, there are doctors and experts for the mind, but back then, we had no idea what words like ‘psychology’ even meant, no idea those kinds of words even existed. It carried no meaning, at least for simple folks like us. And if anyone showed any sign of anything other than what we called ‘normal,’ then they are labelled as mad, or half-cracked, or, in worst cases, possessed. There were no therapies, no medication, nothing that made any sense to do in cases like your mother’s. The only things we had, in fact, the only thing people trusted, was the bible. She was treated as if she had demons inside of her. Different pastors visited, doing the exact same ignorant things—quoting from the bible, delivering sermons about Jesus and His miracles to someone whose foot was tied to a bedpost, trying to pray the demons away. It was pathetic and laughable. Ignorant, all of them.”

Her breathing was loud. Her jawline rippled as she clenched her teeth. Repressed anger gleamed in her eyes as she turned her attention towards the open window.

The tea in my cup had gone cold, half-drank. I set it down on the tray next to her empty cup.

She repositioned the shawl around her rather forcefully, and then took a deep breath and waited for a moment with eyes closed before she turned back to me and spoke again. “The simple truth is—we were all to blame. We, as a community, as a society, failed her. Our unforgivable ignorance, our complete lack of sensitivity, our misguided resoluteness, all had a hand to play. And in the end, when she took her own life, we remarked on the tragedy, reflected on how mishandled everything was, and we professed our sympathy. There was enough sanctimony going around to drown every single one of us,” she ended with a mirthless laugh.

“We were all to blame,” she said again.

“There is one thing I never told anyone,” I said, both surprised and terrified by my decision to share. My hand involuntarily moved, as they often did in affecting moments like this, to feel the scars on my arm. But I stopped myself. “The night before she died, she had a moment of . . . clarity. I never went into the room she was kept in, but that night, I had the urge to go in, just to say goodnight. She was on the bed looking at a newspaper cut-out of the Princess. She smiled when she saw me standing at the door and she called me in. I was afraid. She was usually unresponsive, and hearing her call my name felt . . . terrifying, even though she was calm and smiling. But I went in, and she showed me the picture, and told me all about her. Afterwards, as I was about to leave, she took my hand. There were tears in her eyes, and she tried to say something, and I could see she was struggling to get it out, but no words ever came. Her grip was firm and it was starting to hurt after a moment, and I grew scared. I tried to pull away, but she was much stronger. She held on. Then I started to cry, and then I screamed. I screamed and screamed, but nobody ever came and she never let go. So, I . . . I hit her. I hit my mother, again and again and again, until . . .”

The sun wrapped its warm fingers around me as the breeze carried raindrops from far away, the fairy dusts trapped within them glittering until they fell on soft mossy ground and disappeared without a trace.

“Absolutely none of it was your fault,” I heard a voice say. My eyes were closed and shielded by my hands. The voice went on, but the words became nothing but fading echoes in the wind.

I was held, but I hardly felt it. Kind words were spoken, but I hardly heard it. I was back in the woods, safe under leaves in between the roots. I was safe, I told myself. I thought I was safe. This time, it was all different. The branches were shorter and the leaves smaller. The trees had shrunk and the roots were buried deep beneath. The winds were stronger and the sun harder. And when the travelling rains abated, I knew they would not return. I had to leave the place.

“Really, won’t you stay for dinner?” my mother’s friend asked me again as I stood up from the couch.

“I’d love to,” I said, “but I’ve got a long way to go.”

“I understand,” she said with a kind smile. And as I made my way to the front door, she said, “I understand if it’s not something you want to share, but . . . why are you doing this?”

“What do you mean?” I asked as I picked up my tape recorder from the table and began towards the front door.

“Why relive the past? Talking to all the people who ever knew your mother . . . that’s a heavy undertaking.”

I stopped at the door. “The only way I can move on is to go back. If that makes any sense.”

“Have you spoken to your father?” she asked.

“No,” I replied.

“Will you?”

The sun wasn’t too high above the western horizon anymore, and there were no clouds on its path to sunset. The horizon—a range of wooded hills, the tail end of the Himalayas—was a dark silhouette against the light.

I stepped out of the door and onto the cobbled yard, and I looked back at the woman standing now at the door. The yellow light allowed a forgotten youth to shine through on her skin. For a moment, I wondered what my mother would look like if she had lived to that age. For a moment, I wondered what I would be if my mother had lived. And for a fleeting moment, I wondered if anything might’ve changed at all if the Princess had lived.

“I hope.”

Lian Dousel

Lian Dousel is a writing enthusiast with a bachelor's degree in English. One of his short stories, 'Numbered Days', has been published by Out of Print magazine, and you can find most of his other—non-deleted—prose and poetry on his loosely-maintained blog Gutter Galley.