Her favourite memory was when he dropped her off at the Calicut Medical College hostel and said, “You are the first girl of our family to go to college. Make me proud.”

Illustration by Ajinkya Dekhane

The Dream

“Y’a Rabbul aalameenaaya thamburaane…” A woman, lying on a woven grass mat with its edges worn out, is crying in harrowing pain. Her cries are swallowed by the noise of the pouring rain pattering on the thatched roof of the hut. “I had a feeling it would be early,” Khadeeja whimpered in pain, but told her children to go get the necessities. Her two children, Raziya and Kuttivappu ran about in panic. Raziya was getting clean white clothes and rubbing her mom’s belly. Kuttivappu was boiling the knife to sterilize it.

Khadeeja had a deja vu about this irony two days ago. She was the midwife of Bellikkara; no little foot in that village has ever touched the ground without feeling the callouses of her blessed hands. However, there was no one to attend to her own childbirth. Her only sister-in-law had gone to the big house to attend a birth. Her mother passed away a while ago. Her mother-in-law was bedridden. Her aunts and uncles had gone to Mamburam mosque for the monthly visit. Her husband, Ossan Ahmed Kutti had gone to fetch the Ossathi midwife from the neighbouring village but was caught in the storm. Her little daughter, Raziya rubbed her belly. Raziya thought she would faint at the sight of all the blood. But the presence of her elder brother, Kuttivappu gave her courage. The brother and sister helped their mother deliver the baby.

By the time Ossan Ahmed Kutti had reached the home with the midwife, Raziya had done the job. Thus, her life as an Ossathi attending deliveries began at the age of twelve. She held the crying baby close to her chest, wiping out the sliminess, and thanked God. Kuttivappu, her brother, stood beside her as he always did.

Ameera woke up suddenly. Even though she had woken up from the dream, she could still see the image of her mother, Raziya, as a twelve-year-old standing in the light of the kerosene lamp holding the baby. As she sipped a little water, she looked at Dheeraj, who was sleeping like a baby. She hugged him tight.

“Dream about your mother and uncle again?” He asked without opening his eyes.

“Obviously.” She replied.

In the next thirty minutes, Ameera will get a devastating phone call. But now she looked at the photos on the wall. The one right after the marriage registration with a few friends, and the one when they went to Pondicherry for a short trip. The one where she is pregnant with Arivu and the one after Arivu’s birth. She went to the kitchen and took out the chapatis tupperware.

When the phone rang, she thought of what her mother used to say. No one calls that early in the morning unless it’s news of death or birth. Ameera realized that someone had left the world. She knew no one in the family waiting for the arrival of a new little person. Yet even in her worst nightmare, she never thought it would be her Uncle Kutti. Her neighbour informed her that Uncle Kutti passed away in an accident.

Ameera sat still as the memories gushed in like a mad deluge.

Illustration by Ajinkya Dekhane

The Memories

The calendar on the wall reminded her that it was a Friday. On Friday mornings, Uncle Kutti would trim his beard and then clip his nails. He would sit on the grass mat and extend his legs. The prayer bump on his forehead and the barber’s callus on his shin would shine. He would call her and carefully trim her nails too and scold her for playing in the mud too much. Then he would take a bath, have some rice gruel, and go to Ahsan Maulavi’s house to trim his beard and hair. Maulavi had to look good to deliver the Friday sermon. Then the Maulavi would go to the assigned house for a feastful lunch. Maulavi would never come to eat at Ameera’s house, though. “That is how things are for Ossans. I don’t think it’s right, but… we live with it,” Uncle Kutti would say.

Every day after school, on her way home, Ameera would walk into the new shop.

“Ameera’s Salon, hair and beard cut, Bellikkara. P.O”

She would sit down and watch Uncle Kutti’s magic with scissors. Many a time, she would ask Uncle Kutti to let her play with the shaving foam. He will reason that it is expensive, that it is meant for men, and so on.

Ameera wept on Uncle Kutti’s shoulder on the day her mother got remarried; Or rather succumbed to the pressure to be protected as a wife rather than live as a widow.

“Will my Umma ever be back?” Ameera cried.

“She will… she will pay us visits from time to time.” Uncle Kutti seated her in the high barber chair as he consoled her.

“Why don’t we shave your beard? It looks nasty and might have lice and ticks inside.” He put on a funny face.

“Eww… let us shave it,” Ameera laughed.

They smeared the foam on her face and pretended to shave it.

Years later, when she got the admission card for optometry at Calicut Medical College, it was only Uncle Kutti who stood by her. “Don’t send her to such a distant college; it’s bad for our girls. They better stay close to home,” her neighbours warned.

“Kuttivappu, are you sure about this? It’s too much for our level,” his relatives reminded him. “Why can’t she go to the Mary Matha College here? They have science degrees too.” Her own mother hesitated.

“How will we ever find an Ossan boy for her if she studies so much?” This was the question her late father’s family asked. “My mother is an Ossathi, but my father was a Mappila.” Ameera wanted to tell them, but she didn’t. Instead, Uncle Kutti said, “I will take care of all that.”

Her favourite memory was when he dropped her off at the Calicut Medical College hostel and said, “You are the first girl of our family to go to college. Make me proud.” That was also the painful one, because in four years, when she graduated from college as an optometrist, she would have done the unthinkable: fallen in love. That, too, with a Cheruman boy.

Illustration by Ajinkya Dekhane

The Questions

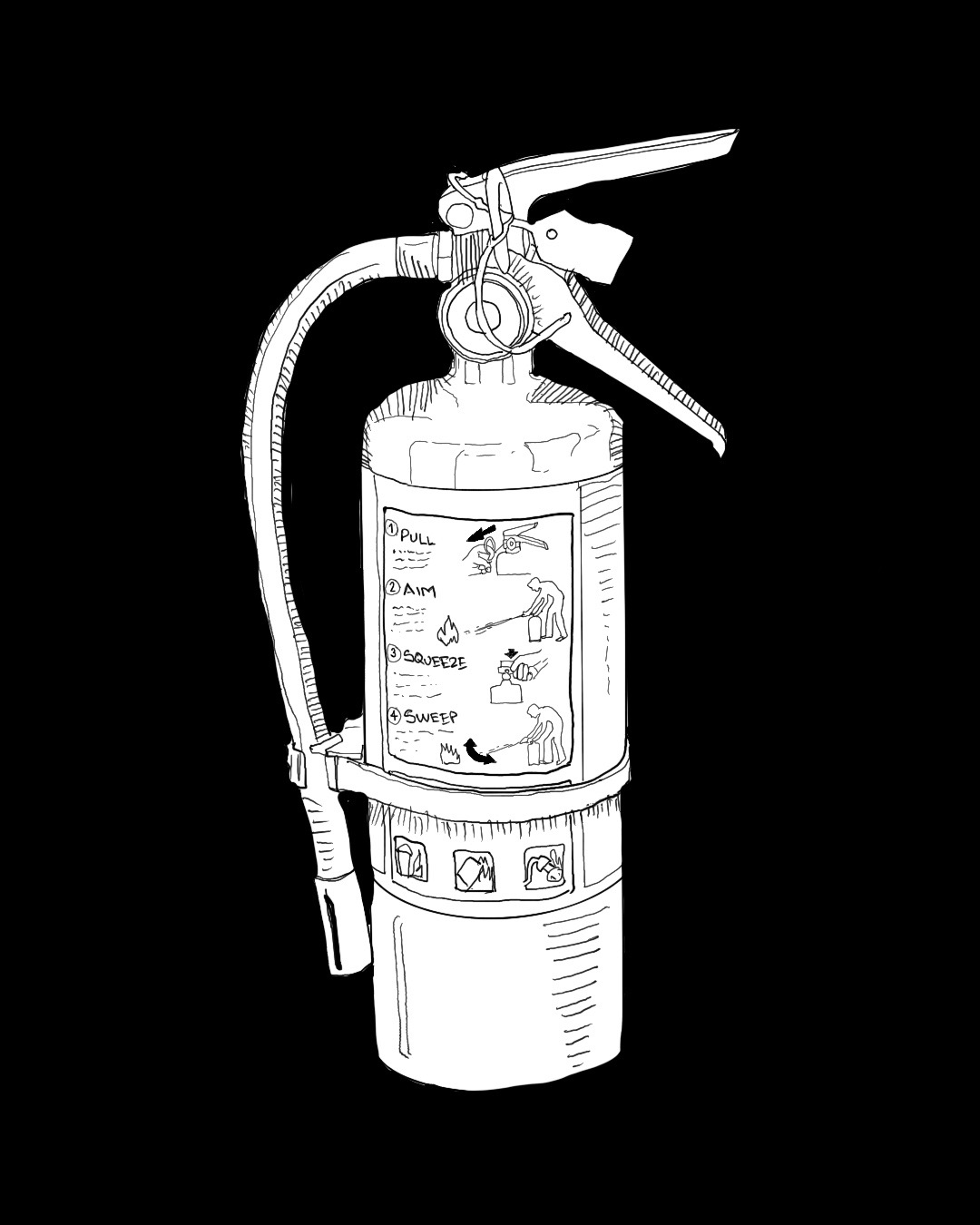

Pull the pin

Aim at the base of the fire

Squeeze the lever

Sweep side to side

Ameera read the label on the fire extinguisher for the umpteenth time. Every time she anxiously waited for the elevator to come up, she calmed herself by reading the label on the nearby fire extinguisher. Now that she has read it so many times, her mind says the words before her eyes read them. But today it felt different. She felt this sudden urge to pull the pin and squeeze it to sweep all around. Her mind was on fire.

It was Dheeraj who said, “Let’s go at once” when he heard the news about Uncle Kutti. He knew how devastating this was for Ameera. But Ameera was fighting her mind ablaze with questions.

Would my family make a huge fuss about seeing Dheeraj there? They would say “The nerve of her, to come back after all this time to mess up her poor uncle’s death with the presence of her non-Muslim husband..whom her uncle hated and didn’t want her to marry…”

Would Uncle Kutti ever want Dheeraj to attend his funeral? Would my mother ask me to leave and not let me see my uncle for the last time? What if Arivu has to see all this? Wouldn’t it scar my little boy forever?

Unlike Ameera’s, Arivu’s questions were enounced.

“Where are we going?” Arivu asked again as they settled into their semi-sleeper seats.

“Bellikkara. That is where your mom was born and lived until we moved here to Coimbatore.” Dheeraj smiled.

“Did Uncle Kutti die there, too?”

“Yes.”

“Did he get born there too?”

“Yes.”

“Where was I born?”

“You know, here in Coimbatore.”

“Where will I die?”

“Huh, now that we don’t know, right? Could be anywhere.” Dheeraj worried that he was answering these questions wrongly. I should have Googled how to talk to children about death, he thought.

“How did Uncle Kutti die?”

“He met with an accident yesterday night.” It was Ameera’s turn to answer.

“How did the accident happen?”

“A lorry hit Uncle Kutti’s scooter.”

“Why did the truck hit the scooter?”

“Well, they said it was because the truck driver slept off by mistake.”

“So what happens when we die?” There was no end.

“When someone dies, they stop breathing. Their body stops working, and they can’t do things anymore.” Ameera answered as she thrust her bag into the rack above.

For a minute, there were no more questions. Dheeraj and Ameera relaxed until they heard Arivu gasp for air. He had pinched his nose and mouth shut and was experimenting with not breathing. “Arivu, don’t do that. It is not good for your body.”

“So where do we go when we die?” Arivu didn’t stop,

“Well…. We’re not sure, but look, they’re selling peanut and ginger candies. Let us buy some, which one do you want?” Distraction is not something Dheeraj approves of, but at that moment, he didn’t know what else to do. He looked at Ameera. She was fiddling with her ring as she always does when she gets tense.

Illustration by Ajinkya Dekhane

The Love Story

He remembered the first time he saw her. It was the Friday evening train. She was smiling awkwardly and fiddling with her ring. Later, Ameera would tell him that she was embarrassed because she thought he had seen her and her friends laughing at him. He was wearing a neon yellow shirt with bright red flowers on it. Her friend Shyama said, “Look at that guy over there; I wonder if this train goes to Goa or something, wearing such shirts. Even my churidar doesn’t have that many flowers.” Ameera had giggled at that joke. Then she thought that Dheeraj saw her laugh and felt awkward.

Every Friday evening and every Sunday morning, they saw each other. They stole glances when the other wasn’t looking. She thought he could wear more pastel shades; he wondered why she couldn’t add some sparkle to her looks. He envied her curly hair, each curl separate and shiny like the fresh tendrils of a cucumber vine. His hair was too frizzy.

One day, as they were alighting the train, he asked her, “What do you put in your hair? It looks so curly and nice.” Ameera felt too awkward, as she didn’t expect him to talk to her. She also saw her neighbour Nafeesu, standing at the station and staring at them. She walked away, not wanting to start any rumours.

The next Sunday morning, she looked for Dheeraj in their usual spot, but he was not there. Finally, she found him in the farthest compartment, and she sat next to him.

“It is aloe vera gel. My uncle Kutti made it for me.” That was the first thing she told him, awkwardly. He laughed out loud. That was the beginning.

Illustration by Ajinkya Dekhane

The Mourning

Uncle Kutti was laid down in the center of the living room. Ameera noticed that the flooring is new. The old red oxide is gone; it is marble now, as white as Uncle Kutti’s kafan robes.

“He looks like a momo,” Arivu said in a low voice. Ameera quickly checked to see if anyone else had heard that. Ahsan Maulavi, who was reciting the Qur’an next to Uncle Kutti, frowned.

He looked up and saw Ameera. She could see the shock in his eyes as he suddenly stopped reciting the Quran for a second. Everyone turned to face the (un)expected visitors because of the sudden silence. Taking a deep breath, Ameera said, “Assalamualaikum.” They all mumbled, “Walaikumsalam.” Or did some of them turn away, pretending not to have heard her?

A woman came forward. It was her mother, Raziya. “Umma,” Ameera sobbed as she hugged her mother after a long twelve years. “You are too late,” Raziya cried. That is when Raziya noticed Arivu. Her face beamed with affection as she extended her hand lovingly towards her grandson, whom she had silently longed to meet.

Once they reached the hotel in the nearest town and got freshened up, Dheeraj told her that he was not coming right away. She knew why but still asked. “Your returning after so many years would be a big moment in itself. My presence would make it more dramatic. You go with Arivu and let me know how it goes.” Ameera hugged him and said, “Thank you”.

Raziya and Ameera sat in their old bedroom. “Did he ever ask to see me?” Ameera asked, swallowing a lump of pain in her throat.

“He was unconscious when they brought him to the hospital. He never really woke up.” A tear streamed down Raziya’s left eye.

“What about before the accident? Did he speak about me?” Ameera yearned.

“We never speak about you here. It is like even hearing your name was so hard for him.” Raziya spoke slowly. They both looked through the window, at Arivu, watching the mother hen peck food for the little chickens.

“Once… once he mentioned you. But I don’t think you would want to know that.” Raziya hesitated, but Ameera pressed. “When Sumeira passed the twelfth, she said she wanted to go and learn some fashion technology courses in Kochi. But Vappu didn’t let her. Then, Sumeira being Sumeira, made a big fuss, and Vappu burst out, saying, “I don’t want another Ameera here.” Raziya cried.

Although she wanted to, Ameera couldn’t cry. Her body swelled, her eyes caught fire, and her heart broke.

Illustration by Ajinkya Dekhane

The Funeral

Once almost everyone had seen the body, Ahsan Maulavi stood up and asked if there was anyone left. That is when Sumeira entered, rushing in. Ameera watched as her little cousin, now a tall, beautiful woman, kissed Uncle Kutti on the cheek. She also heard two neighboring women whisper. “It is her own father, and she is not even crying.”

“Let us then take the Mayyith,” Ahsan Maulavi said. Ameera felt a chill run down her spine when she realized how a human who lived a wholesome life just becomes a nameless ‘dead body’ after death. The gathered Ossans came forward and lifted Uncle Kutti. Ameera tried to sit next to Sumeira to talk. But Sumeira walked away silently.

Hours later, Sumeira asked as she sipped a bitter black tea in the kitchen yard, “Ami, do you remember me?” Ameera couldn’t decide which was more piercing: her stare or the question itself.

“What kind of question is that, little sister?” Ameera asked back.

“When you fell in love and everything, you forgot me. You left me here. Do you have any idea how hard it was without you?” That was when Sumeira cried. She rarely cries in front of someone else.

“I know. I know. Do you think it was easy for me?” Ameera wanted to tell it all—about how heartbreaking it was to realize that the one person whom she thought would understand why she wanted to live with Dheeraj—her uncle Kutti—let her down… about how she struggled with work and pregnancy after Dheeraj was unexpectedly laid off and was out of work for months.. about how they could hardly find a house to rent without pretending to be upper caste… about how she longed to come to the home she felt she had lost when she chose her love.

Sumeira had a lot to tell too—about how she never understood why her elder sister-cousin left without saying goodbye… about how her father would never let her go see Ameera… about how Ameera’s choices made her choiceless… about getting married too young and then divorced too young… about coming home as a divorcee and then going back to college and then trying to build a business out of her passion for hair styling… about how everything she does will not be enough as long as she is just a divorced woman.

But they didn’t. Ameera took the glass of black tea from Sumeira and sipped a little. “Thfoo!” She spat it out. Sumeira laughed as Ameera added two spoonfuls of sugar to sweeten the bitterness.

Illustration by Ajinkya Dekhane

Another Love Story

Raziya fed Arivu ghee, rice and beef. They had bonded rather quickly. She looked carefully at his bushy eyebrows and big earlobes. They reminded her of him, her first husband but only lover, Kunji Muhammed Koya.

When she was fourteen, her father passed away. She was sixteen years old when she went to the big house of Bellikkara to attend a birth. She had gone there with her mother once before to get rice for Eid. But the interior of the house fascinated her. She lost count of the chambers and the silverware. The birth went smoothly, and the big mother of the house really liked how clean, diligent, and dexterous Raziya was. “You look too pretty to be an Ossathi,” she was told. For the next forty days, Raziya had to come in to bathe the mother and baby, smear the oils, and massage.

It was on the eleventh day that Kunjimohammed noticed Raziya. Initially, he thought she was some distant relative who had come to stay. Later, when he realized she was an Ossathi, that didn’t change his ardent feelings for her even a bit. Raziya, on the other hand, was too scared to even look at him. But once she did, she couldn’t look away.

When it was revealed that the young Koya and the Ossathi girl are in love, hell broke loose. His parents tried their best to dissuade him. His aunts recited Quranic verses and prayers while they cast off evil by throwing salt and red chillies into the hearth. They said the Ossathi girl tricked the boy with her charms. His uncles said she must know some nattumarunnu to entice men.

The one who actually tricked someone was Kuttivappu. He tricked the new Maulvi in the next village to do his beloved sister Raziya’s and Kunjimohammed’s nikkah. When Kunjimohammed came home to take Raziya with him, Kuttivappu brought a small mirror. As Ossans do for every local wedding, Ossan Kuttivappu held it to face the bridegroom, Kunjimohammed, and handed him a small comb. Kunjimohammed took the comb, combed his hair well, and handed it back with a reward of cash.

The Nikkah didn’t end the lovers’ plight. The Koya family pressured Kunjimohammed to talaq Raziya first, and if not, to marry a second wife. The big mother of the big house said bringing in a good woman would undo the impurity of having brought an ossathi home. Kunji Muhammad died a year later from a stroke, putting an end to all their attempts. Despite being pregnant, Raziya tended to him day and night but none of her herbs and prayers could rescue him. After three months, Kuttivappu took his sister home and she would visit the big house rarely, only enough for Ameera to know where her father came from.

Illustration by Ajinkya Dekhane

A Special Marriage

Dheeraj came from a village near Bellikkara. He took Ameera home one evening to meet his mother. While Amma received her happily, she also shared her worry about their marriage plans. “Will your people hurt my boy?” Amma had asked Ameera. In no time, Ameera would know that her people were capable of not only hurting him but also her.

It was her paternal cousins who threatened and thrashed Dheeraj. They never really cared for her, but they cared for the pride of their tharavaadu, apparently. Then came Kuttivappu’s words. “I raised you to go live with a Cheruman?” Uncle Kutti exploded.

“Why would you say that? So, you let your sister choose her husband but not me?” Ameera was calm.

“Your father was a Muslim. Dheeraj is not.” Uncle Kutti said firmly.

“I love him. I want to marry him.” Ameera stated strongly.

“Then, leave my home at once. You are not my daughter anymore.” Uncle Kutti was stern too.

“What if he was not a Cheruman? “But if it had been a Namboori or a Nair, would you have been okay with it?” Ameera didn’t give up.

Uncle Kutti stared at her. She didn’t blink, either.

After a few minutes’ pause, Uncle Kutti slowly said, “I don’t know… no. I… I don’t think so.”

“Yet, it took you some time to think, huh? took so long to say “no.”” Ameera looked away

Ameera knew that Uncle Kutti always dreamed of getting her married to an educated man from a rich family. Yet she thought he would understand her choice despite everything. When things didn’t go the right way, she fled to Coimbatore with Dheeraj.

Illustration by Ajinkya Dekhane

The Heritage

Now, that she was back after more than a decade, Ameera breathed in the air of home. It didn’t feel like home yet, but rather like an abode of ambivalence.

“Was Aqiqath done for this boy?” Nafeesu, their neighbour looked at Arivu and asked Raziya.

“No,” Raziya mumbled.

Arivu heard it and asked, “What is Aqiqath?”

“Uhm, it is a tradition to shave a newborn’s hair and sacrifice a goat or a buffalo.” Ameera quickly explained.

“What about Sunnath? You did Sunnath for him, right?” Ibrahimkutty, the local caterer, was asking as he made biryani for the after-death function.

“No,” Ameera answered.

“Oh, God! Not even Sunnath!” Nafeesu covered her mouth in shock.

“What is Sunnath?” Arivu asked again.

“Well, it is a procedure to remove the foreskin…hm.. of..”

Arivu jumped in. “Oh, I know! My friend Rahim told me.”

“Sigh, yes, that.” Ameera missed Dheeraj badly.

Raziya went inside. Ameera followed her. They saw Sumeira put up a framed photo of her father on the wall.

“I’ve never understood why Uncle Kutti would support your wedding but not mine… all because of a religious difference? I think this is because Dheeraj is cheruman. Uncle Kutti, of all people!” Ameera said to Raziya.

“Probably because he saw how choosing to live with someone outside the community ruined my life.” Raziya sighed.

“I think he wanted the best for you. It broke his heart when you didn’t listen to him.” Sumeira said as she steadied the frame.

That’s when Arivu came in. “Look what I found!” He had a box with him, an old one with oil glistening over the rusty edges. “Here is a knife and a pair of scissors. “There are also some brushes.”

Sumeira said with a smile, “That is uppa’s. His ossakatthi and other tools.”

Arivu asked, “What is that?”

Raziya led him “Come with me, I will tell you as we have some lunch.”

Ameera warmly watched the grandmother and the grandson walk away.

“You badly need a haircut.” Sumeira said as she pulled Ameera into the bedroom.

She washed Ameera’s curls and trimmed the ends with her father’s scissors. Then she brought in a small container. It was labelled ‘aloe vera gel’.

“You are so good at this.” Ameera smiled at Sumeira as the hair dried.

“I know.” Sumeira winked.

The Reality

Ameera looked at Uncle Kutti’s table. Everything was kept prim and proper. His Qur’an, with the green satin cloth with golden tassels wrapped around it. His tasbeeh mala. His book of old Mappila and Malayalam songs. His papers, spectacles, kerchief, and everything.

She opened the table’s drawer. There was his old leather wallet. She opened it curiously. She remembered that he used to keep a passport-sized photo of her there. She couldn’t find the photo in the wallet. Ameera felt a soaring pain under her belly. “It was so old, and it was probably so worn and torn that he had to throw it away.” She tried to console herself.

Then she saw a thick piece of paper stuck in between the currency notes. She took it out. It was a small colour printout of a picture of her, Dheeraj, and Arivu—one she had posted on Facebook two months ago. Ameera smiled as she put it back in. She took her phone and called Dheeraj. As soon as he picked up the call, she said,

“Come home”.

Glossary

- ‘Y’a rabbul aalameen’ means ‘Oh the Guardian of the worlds’ in Arabic and ‘Thamburaan’ means Lord in Malayalam, the native language of Kerala.

- Ossans and ossathis constitute a (‘caste-like’) section of South Indian Muslims especially in Kerala; the Ossans are traditionally barbers and circumcisers. The Ossathis, the woman of the community are midwives and engage in pre-natal and post-natal care. They are considered lower in the social hierarchy of Kerala Muslims.

- Ossans used to rub the knife along their shin while cleaning it, which create a callus overtime.

- The Cherumans are a Dalit caste of Kerala, who were oppressed as agricultural serfs under feudal upper-caste landlords.

- Kafan refers to the enshrouding of a dead Muslim person in clean white clothes.

- Nattumarunnu mean herbal medicines and other home-based remedies administered on the basis of traditional knowledge.

- Namboori also called Nambudiri, are the Keralite Brahmin caste, occupying the supreme rung of the social hierarchy. They are feudal landlords.

- Nairs are an aristocratic caste of Kerala, constituting a position lower than the Namboodiris in the hierarchy, who were traditionally involved in military services.

- Aqiqath is the Islamic tradition of slaughtering an animal and donating the meat on the occasion of the birth of a child. This non-mandatory but advisable practice is combined with the shaving of the hair or the naming of the child according to local cultures.

- Sunnath in the Keralite context of circumcision denotes the ceremony of circumcising a Muslim male, by removing the penile foreskin. The local ceremony is attended by relatives and neighbours and includes presenting the boy with gifts and also feasting. Traditionally, the ossans used to perform the circumcision which eventually shifted to hospitals and are conducted by doctors, following the advent of modern medicine.

- Ossakatthi literally translates as the ‘barber’s knife’, the knife the barber uses to cut hair and so.

- Tasbeeh Mala is a string of beads used to count the chantings of prayers said in the glory of Allah, the Islamic conception of God.