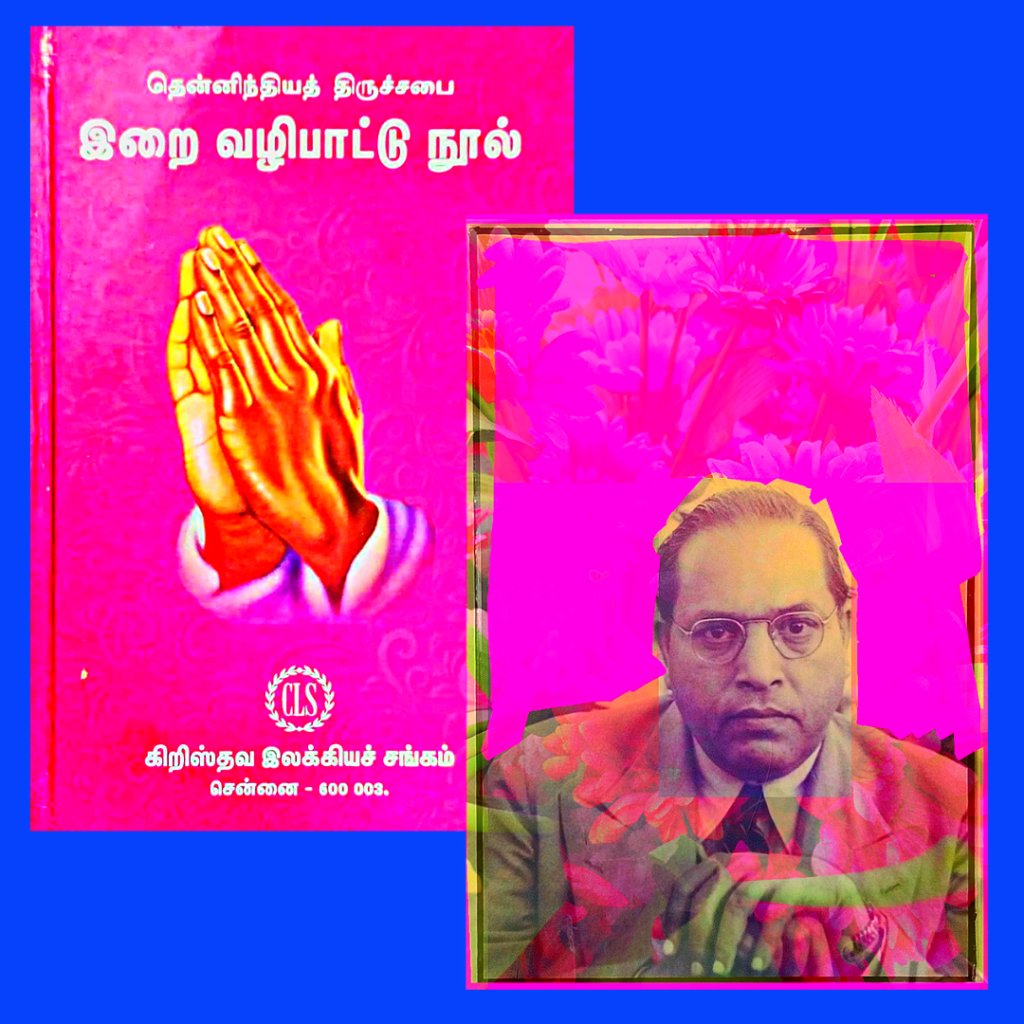

My friend, Rev John Boopalan, a Dalit liberation theologian, told me that most Christians come to Ambedkar through Jesus. A fiery leader who sacrifices everything, life and death, for his people’s liberation. Not a comparison on a facetious level but for recognition like an arrow through the heart.

Artwork by Riya Talitha

IN the beginning, I thought I’d just write a standard chronological personal essay. How I grew up lonely and occluded to myself, missing the knowledge of an essential part of my political and community identity. Then the story of how I ate from the Tree of the Knowledge of Dalit Identity and whet my (longstanding) consuming hunger for belonging in Ambedkarism. My own little genesis, a neat exodus from the haze of Christian culture.

But whether I like it or not, Christianity is the muscle memory & blood ritual that enlivens the bones of my world. My past is a ghost I can’t ever bury, and my God won’t ever just stay dead.

The Eucharist, the Holy Communion, the Lord’s Supper – whatever you call it, it’s at the heart of Christian worship and one that only baptised or confirmed believers can partake in. I’ve seen it administered by cassocked Church of South India pastors from red and gold altars, and I’ve seen it done in school auditoriums with Tropicana grape juice and wafers. It’s a memorial of Christ’s death and resurrection and is supposed to evoke his very presence. It is the central sacrament in the Anglican doctrine of my family and follows a particular Order of Service, a basic pattern laid out in our Book of Common Prayer. It’s a familiar and ancient liturgy, and I’ve always wanted to conduct it myself, so I guess this is my chance.

So, take ye and eat –

THE PREPARATION

August 2019, New Delhi

I spent the summer after my second year at university in a small office bathed in warm yellow lights, blasting music in my headphones and copy-editing research papers. The first full manuscript I was responsible for was Dr Roja Singh’s Spotted Goddesses: Dalit Women’s Agency-narratives on Caste and Gender Violence – a scholarly exploration of folksongs, oral traditions and community mythologies of Dalit women in Tamil Nadu.

This book made my world hollow and illusory. In the last chapter, Singh shares her account of being a Christian woman grappling with the (re-)discovery of her Dalit identity while doing fieldwork for Spotted Goddesses. “I was born in Vellore, Tamil Nadu,” wrote Singh, freeing herself, shedding her shame. I read – “My ancestors converted to Christianity like many other Dalits in the area due to missionaries from the Church of Scotland”.

The day I read Spotted Goddesses, I tremulously asked my parents, are we upper-caste? They looked at each other and burst out laughing.

CALL TO WORSHIP

Artwork by Riya Talitha

I was born in Vellore, Tamil Nadu. My family moved to New Delhi when I was six years old. Going from a well-knit community to an isolating city had a telescoping effect on my sense of self and belonging. When I started thinking about my Dalit identity, I felt distanced from it – not because I hadn’t experienced casteism but because I hadn’t recognised it. I also got the sense that other Dalits didn’t think we counted, which isn’t too different from the general Indian Christian experience.

We hardly recognise ourselves, fractured and divided; the fabric of our lives is a sustained tapestry of delusions; we think we can pray the whole world away, a culture of electoral & political disempowerment and yearly spiritual retreats. As though our whole community identity isn’t one of retreat. Rootless, insular and invisible, the wider world doesn’t recognise our philosophies, histories, or selves outside of tired one-dimensional stereotypes.

Except for Ambedkar, habitual in his unexpectedness. He ends Christianising the Untouchables, with “I am deeply interested in Indian Christians because a large majority of them are drawn from the untouchable classes. My comments are those of a friend.”[1]

THE LAW & THE PROPHETS

Just a few months ago, the Supreme Court asked the Centre to provide its current stand on the issue of extending the benefit of SC reservation to Dalits from Christian and Muslim backgrounds. It is highly contentious for a decades-long case petitioning for just the bare minimum of reservation. The only reason it’s even made it to the Supreme Court is years of protests and groundwork laid by Dalit Christian and Pasmanda groups.

In Tamil Nadu, we already have these provisions because of Iyothee Thass, the first to enter the word ‘paraiyar’ into political vocabulary. He didn’t consider it a slur or want to reclaim it. His solution was to propagate the term ‘Adi-Dravidar’ as an official government term that refers to paraiyars in Tamil Nadu. So, Tamilian Dalit Christians can get SC status as Adi-Dravidar Christians. [2]

Thass was a Buddhist convert, but his language has a delightfully biblical sense of import. He’s famous for calling Paraiyars the “disinherited sons of the soil.” Whatever the historical truth of these communities, these contested pasts of my forebears, you must acknowledge the political shrewdness of these claims, this show of strength.

“…I want them to be strong because I see great dangers for them ahead. They have to reckon with the scarcely veiled hostility of Mr Gandhi to Christianity taking its roots in the Indian Social structure. But they also have to reckon with militant Hinduism masquerading as Indian Nationalism. If newspaper reports are true, a crowd of mild Hindus quietly went and burned down the Mission buildings in Brindaban and warned the missionary that if he rebuilt it, they would come and burn it down again?! If it is the shadow of events to come, then Indian Christians must be prepared to meet them. How can they do that except by removing the weaknesses I have referred to? Let all Indian Christians ponder.”

– Dr. B.R Ambedkar, Christianizing the Untouchables

Ambedkar’s questions are piercing and double-edged. In later works, he thinks that while Islam, Sikhism and Christianity centre equality doctrinally, in practice, they have been infiltrated by casteism. That’s one of the reasons he makes his case for Buddhism to be the path to Dalit liberation. However, there’s no reason we all have to fall in line and convert to Buddhism. Quite apart from his denigration of devotion to “great men”, he was no messiah, no god incarnate.

It doesn’t matter what the ‘truth’ of our ancient past is. Whether we were Buddhists brought low by conquering Aryans or if we’ve been indentured & landless since time immemorial. The function of caste is that our histories are fragmented, while the overriding principle of anti-casteism is that we get to choose our destinies.

THE MINISTRY OF THE WORD OF GOD – EXHORTATION

It’s like this. From Karl Marx to the local DU Leftist guy, people always pick at Christianity’s preoccupation with “the world to come”. And this sort of evangelically-tinted obsession does foster complacency and inaction and slots neatly with elite interests.

Whenever Christianity is propagated as a dominant religion or as the banner of colonising conquering efforts, it spreads through collaboration with local hierarchies and wholesale repression of insurrection at a spiritual level. In his Discourse on Colonialism, Aimé Césaire wrote about the “crowning barbarism that sums up all the daily barbarisms…that engulfs the whole of Western, Christian civilisation in its reddened waters, and oozes, seeps, and trickles from every crack.”

In the Indian subcontinent, it is undeniable that so many of the Christian and Catholic traditions are reifications of the Aaryan impulse counter-mingled with the heady drug of Western Christian civilisation.

But I’m talking about faith. Faith as a material response to the reality of suffering, an attempt to provide, if not actual respite, then at least the hope of it, someday. When people and institutions try to game-ify this hard truth by either laying it into a vast cosmic map where everything seems to make sense or selling exclusive escape tickets, it’s just lousy theology . [3]

“The Christian Church teaches that the fall of man is due to his original Sin and the reason why one must become Christian is because in Christianity, there is the promise of forgiveness of sins. This is exactly what has happened with the untouchable Christians…When he was a Hindu, his fall was due to his Karma. When he becomes a Christian, he learns that his fall is due to the sins of his ancestor. In either case, there is no escape for him. One may well ask whether conversion is a birth of a new life and a condemnation to the old.”

– Dr. B.R Ambedkar, Christianizing the Untouchables

– Dr. B.R Ambedkar, Christianizing the Untouchables

Artwork by Riya Talitha

“This devotion of yours is for the sake of heaven, while I desire that the ills of life on earth are probed, and a solution found” writes Ambedkar in Buddha and His Dhamma describing the Buddha’s reaction to Brahmin practices of penance and mortification; torture and denial of the body, of material comforts.

Growing up, I was made to feel like the biggest screw-up, the biggest sinner, rolling in the filth of my inherent moral decay – a bad kid, a disappointment of personality and potential. I was made to mistrust my judgement, even though I have never led myself wrong. Church messed with my mind and self-esteem and condemned my turbulent mental state as proof of my inherent sinfulness. Even when I knew that wasn’t true, that’s what it often felt like.

The thing about religious guilt is that it screws you up and distorts you to yourself. It makes it hard for you to recognise yourself, to see yourself truly. And crushing, punishing guilt used to be my default reaction to everything.

THE GREAT THANKSGIVING

People have templates for dealing with dissatisfied young Christians. They share smug little anecdotes about God’s Plan when they’re not telling you to pray it away. They avoid politics and mental health by discussing the importance and value of a Jesus as a personal saviour. It would be a far more typical story if I had always been angry about the church. If I had gone through a teenage atheist phase, asking impertinent questions to pastors and fighting with elderly relatives about Tumblr social justice issues.

But, the truth is, I used to be a bloody little zealot. A tormented firstborn son; I’d have had my neck on any available altar at even a hint of a sign. I wanted a God I could bite into. I couldn’t get

enough of Christianity. I had read the entire Bible by the time I was fifteen. It was always clear to me that messianic symbols in the Old Testament [4] were stories of dissatisfaction, confusion and questioning.

Voices arise from the wilderness, from captivity and exile, in bitterness and accusation, refusing to be comforted.

Jonah resents God’s judgement, even after three days in the belly of the beast.

Jacob wrestles with God and is rewarded with the sight of a ladder of angles going up to heaven.

So no one could fob me off with simple American-evangelical(-yeehaw!) interpretations that see the pursuit of justice as a footnote to the central passage on personal fault, on sin. My problem was that I never let anyone sideline the issue. I was very young. I prayed all the time because I was very angry.

WORDS OF INTERCESSION

My friend, Rev John Boopalan, a Dalit liberation theologian, told me that most Christians come to Ambedkar through Jesus. A fiery leader who sacrifices everything, life and death, for his people’s liberation. Not a comparison on a facetious level but for recognition like an arrow through the heart.

I’ve always leaned into the mysticism of Christianity. It’s hard to take great comfort in miracles, feats of individual faith, and little quizzes that are supposed to show you What Your Spiritual Gift Is. It’s so much more real to me that there have been acts of great wonder that are unreplicable and immutable. Stories that reverberate through history down to me. Rituals without props or costumes given power because of how people have followed them. Symbols that have changed the course of their lives.

A baptism at the banks of a river, a dove in the sky, two cousins reaching out to each other.

A man cups his hands and drinks water from a tank. A multitude of 10,000 follows him.

THE SACRAMENT OF THE BODY OF CHRIST

Artwork by Riya Talitha

The real gospel is about transformation. Apparently, Dalit and lower-caste mass conversions used to confound several European missions, which is ironic considering the numerous mass conversions in the Bible. Jesus was baptised as part of a mass, as were many of the early apostles.

Ambedkar understood the power and rebellion inherent in mass conversions. He saw the far-ranging insurrection they symbolised and made real. [5] I don’t know how exactly my ancestors converted. We have a few stories and educated inferences, which ultimately don’t matter to them or me. Their choices are not meant to constrain or direct my life.

I’m interested in the stories of family members whose lives are still in living memory because they influenced and were loved by people I love now.

I love hearing about Thotho, my mother’s grandfather. He was the principal of a teacher training college in my hometown. He wore khadi, loved Shakespeare and Ambedkar, and joyfully called himself a “beef-eating Dalit from Orathoor”. Everyone says he would have loved talking to me.

I love hearing about my father’s grandmother, Pattima. She raised him and cultivated his education and potential because she once dreamed of him as an adult getting on an aeroplane. She immediately shifted him from his Tamil-medium school to an English-medium one because if he was going to be an important man, he had to reach for the sky with open hands.

I don’t think we need to look past living memory to find some essential proof of worthiness or humanity. Why do we need legends of military prowess or mythological ethnic pride to bolster our identities? Our pasts might not be glorious, lettered with outright militant rebellion, but the future is ours to claim. What’s freedom worth if you have to keep looking back?

When I first started reading Ambedkar, I was immediately envious and admiring of Ambedkarite youth who’d grown up in the movement. They seemed so much more self-assured and confident than me. Their arguments were considered, their anger and words appropriate – not incessantly guilty, scared of messing up. I spent a whole year wondering if I should convert to Buddhism too, wondering if I’d ever really be fully Ambedkarite with this faith that seemed so full of brahminical standards and sensibilities. Doubting if I could ever be that free.

THE BLOOD OF THE NEW COVENANT

September 2019 – July 2021: Unceded, ancestral territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations (otherwise known as Vancouver, Canada).

To be fair, this was also the culmination of my multi-year crisis of faith. I felt faithless in my body, down to my bones. It choked me to pray; I found it hard to look my parents in the eye. Patriotic, till it was ripped out of me, till it was immoral to hold on. I held on to the police state that I didn’t know India was for longer than I held on to Christ.

I took some time off. I rested, studied, explored and worked. In so many ways, I’d been made new, rubbed raw and bloody. Brimming with new ideologies, an entire college degree (!), books, connections and skills, and then August came around, and then news that Fr Stan Swamy had died

– –

When Fr Stan Swamy died

– –

When Fr Stan Swamy was martyred, I was too furious to think. An emergency alert from my university said there was a continent-wide heatwave; an entire town burnt up like a Biblical plague; please drink water. I didn’t sleep for two days. I remembered the tiny gold crosses that girls in Vellore wore. My mother saying she’d always felt we existed on the sufferance of Hindu society. I thought of my first comic book, this sepia-tinted volume about the life of Christ from birth to death and resurrection. The title alone thrilled me to my core when I was small. I’ll be honest; it still does.

ANAMNESIS – THE PASSION

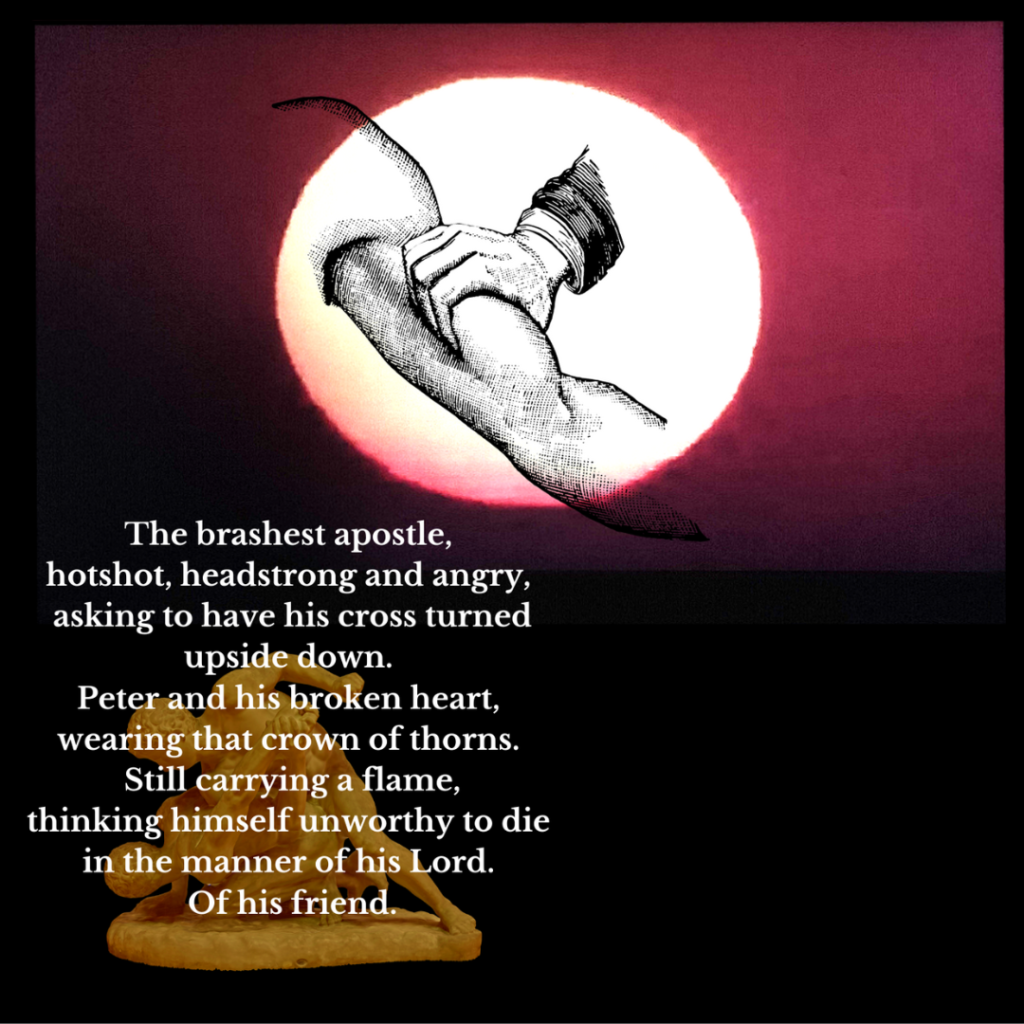

When I was ten, the History channel used to play this movie about Saint Peter’s life & ministry right until his crucifixion. I watched re-runs of this frankly intense film over and over again, transfixed by my favourite apostle.

Artwork by Riya Talitha

Simon Peter – a fisher of men. Peter the rash, Peter the bold. Peter, the rough, first to speak, first to draw his sword, first to drop to his knees. Peter – CEPHAS – the rock on which the church is built.[6] Often arrested, frequently imprisoned, he was killed and blamed as a conspirator behind the Great Fire of Rome. The brashest apostle, hotshot, headstrong and angry, asking to have his cross turned upside down. Peter and his broken heart, wearing that crown of thorns. Still carrying a flame, thinking himself unworthy to die in the manner of his Lord. Of his friend.

Almost two hundred years later, Tertullian, a father of the early church, writes, “Peter endured a passion like his Lord’s.” [7]

ANAMNESIS – THE RESURRECTION

Jesus didn’t experience all human suffering. The Romans offered Jesus a wine-soaked rag when he cried out in thirst. Fr. Stan Swamy didn’t even get a sipper.

Jesus didn’t die to fulfil a prophecy. He wasn’t brought low by karmic inevitability. He was killed as an insurrectionist and rabble-rouser; any other interpretations take away from his agency, his very bodily autonomy.

In 2019, a year after he was charged with criminal conspiracy, Fr Stan gave a speech about the Jesus he followed – Jesus of Nazareth, who lived the life of a revolutionary, accused of sedition and cruelly crucified.

ANAMNESIS – THE ASCENSION

The question of who can claim Dalit identity may be deeply contested, as is the debate on whether it should even still be claimed. But surely Ambedkarism is about leaving, right? In What Path to Salvation, Ambedkar addresses doubts ‘Hindu’ Dalits may have about the political viability of conversion as a means of liberation and attaining empowerment. He argues that the fact that Muslims and Christians have differentiated themselves from Hindu society is what makes political safeguards something they’re owed. “Because [their] religion is different, [their] society is different,” he writes, pushing for his people to leave Hinduism behind too.

Ambedkar isn’t wrong. I like the clean break.[8]

‘Casteless’ churches misinterpret whose suffering the Bible is soaked in. Fearing persecution when no one is after you is paranoia. Drunk on the old wine of purity and pollution, they call privilege a divine blessing and make a mockery of their new wineskins.

I can’t stand their self-righteous cowardice anymore. But the early Christians have a hold on me. Running, hiding, lying through their teeth. Scrabbling around Rome’s graves, carving their queer symbols, staring down lions and gladiators. Salvation is Christ’s, but the line is held by the love of his friends – going onwards in his memory and dying in his name to this day.

What are Jericho and Rome to faith like this? What are Jerusalem and Delhi, for that matter?

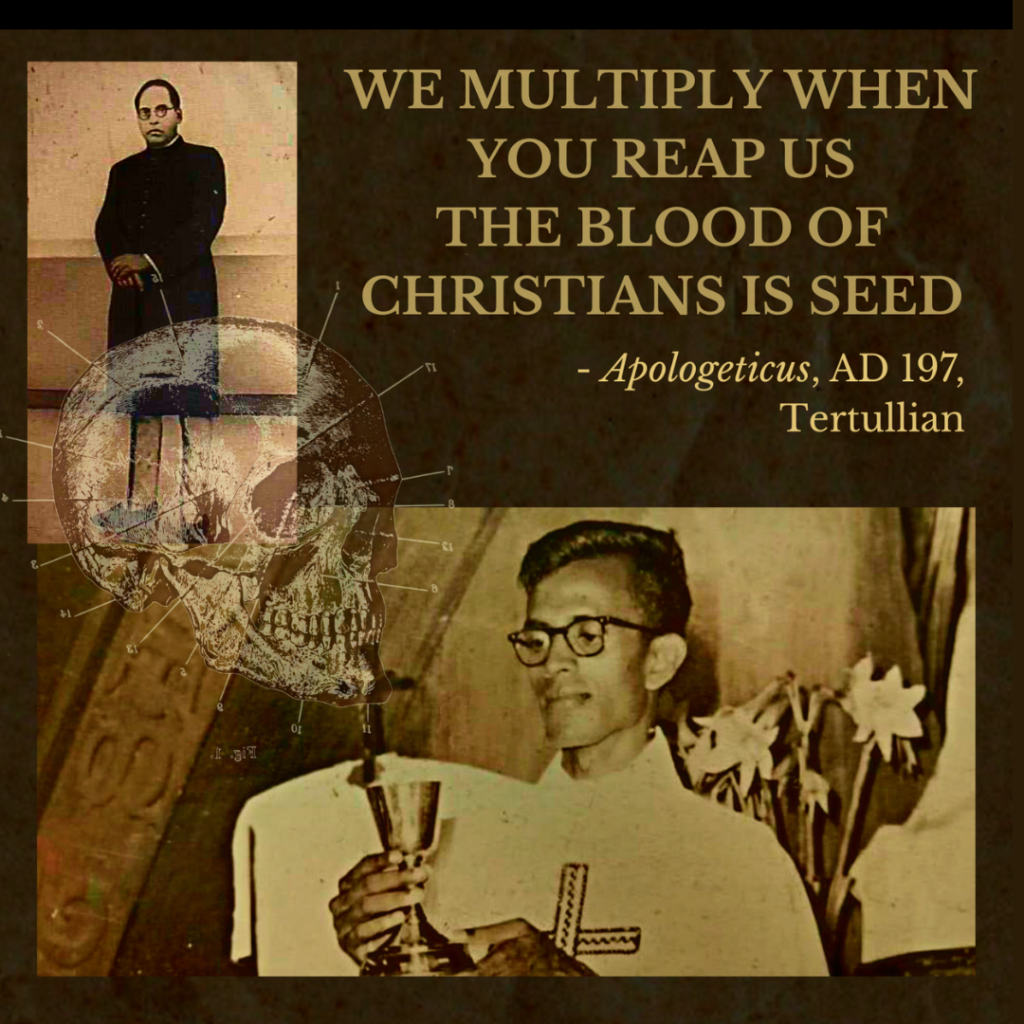

AD 197. Carthage.

Newly converted, Tertullian writes what will become a foundational doctrinal text. Apolegeticus was a public letter to the regional bureaucrats, protesting the means and mechanisms of bigotry against the church. The massacres, lies and unjust laws burnt within him.

“We multiply when you reap us”, he wrote. “The blood of Christians is seed”.

Artwork by Riya Talitha

EPICLESIS

The epiclesis is the most sacred part of the eucharist because it invokes Jesus’ own words. He breaks the bread and shares the wine at his Last Supper, symbols of what will be known as the doctrine of transmutation. ‘Do this in memory of me,’ he said, hours before his impending arrest, days before he died and came back to life.

“Religion isn’t a piece of ancestral property,” writes Ambedkar in The Untouchables and Their Destiny. Ambedkar’s criticisms of Hinduism ask questions about equality, the possibility of kinship, and the obligations of love, respect and fraternity. The mad dogs of orthodoxy howl for his blood; he’s the snake in their poisonous garden because he broke through their lies and showed a means of transmutation for his people.

“To use the language of the Bible, for the race of life all are called, but only a few are chosen. Most downtrodden men fail to achieve greatness in this race of life because they have not the courage nor the determination to sacrifice the pleasures of the present for the needs of their future…It is struggle and struggle alone without counting the sacrifices or sufferings that will bring their emancipation. Nothing else will. The Untouchables must develop a collective will to rise and resist. They must believe in the sacredness of their task and should join in prayer and say:

“Blessed are they who are alive to the duty of raising those among whom they are born.

Blessed are they who vow to give the flower of their days; their strength is of soul and body and their might to further the campaign of resistance to slavery.

Blessed are they who resolve-come good, come evil, come sunshine, come tempest, come honour, come dishonour – not to stop until the Untouchables have fully recovered their manhood.”

– Jai Bheem, Madras, Dr Ambedkar’s Birthday Special Number, 13 April 1947.

The doctrine of transmutation means change, alteration or, in other words, conversion. What my family passed down to me isn’t mere ritual or hollow religion. My real inheritance is a life unencumbered by shame and fear. Why shouldn’t I be proud of that?

COMMUNION

The Acts of the Apostles is a thrilling read. It’s the sequel to the four gospels – Jesus’ life and ministry, his death and resurrection, from four different apostolic perspectives – and follows the events after his ascension to heaven.

By the time you get there, where the disciples are standing around, staring up at the sky where their friend has left them, you’re familiar with them. Their witness convinces you that they saw the fulfilment of the Messianic prophecies with their own eyes.

And then the next day, while they sit, perhaps shell-shocked, maybe grieving, maybe afraid, a great wind rushes amongst them, leaves tongues of flame on their heads; the presence of God among them.

This is the first Pentecost. The urgency with which they allow this to change their lives! The way they cast their fortunes with one another! The frenzy, the life-changing brotherhood, the multitudes of languages and fire without burning. It fits so well when I later find out that some of the largest churches born through mass Dalit conversions are Pentecostal churches.

BENEDICTION & RECESSION

I think a lot of us have lost the plot. We must confront the reality of caste in the church, history, and ourselves. We must engage with Dalit Christian lifeworlds and Adivasi Christianity spiritualities. We need to be resurrected into the world because life isn’t demarcated into politics, church time, and other neat little categories.

In Christianising the Untouchables, Ambedkar laid out the problems wrought deep in the foundations of the Indian Church. He asked questions we still struggle to answer because they’re a driving sword cutting into the meat of our faith. The writing is on the wall; those who don’t wake up have already been found wanting.

In a famous passage in the Book of the Hebrews, St Paul lists the heroes of the scriptures, “who through faith subdued kingdoms, wrought righteousness, obtained promises, stopped the mouths of lions. Quenched the violence of fire, escaped the edge of the sword, out of weakness were made strong, waxed valiant in fight, turned to flight the armies of the aliens..” [9]

I think what is being asked of us is very clear, and even clearer – who exactly are those who refuse to answer the call.

CLOSING HYMN

When I was younger, Christ seemed impossible to live up to and relate to. The New Testament was supposed to be a manual for everything, and needing more than it wasn’t encouraged, whether in matters of justice or solace for the deep sadness that has plagued me all my life. So, I had to walk away and find my bearings.

Lately, though, there’s a wind blowing that I haven’t felt for years.

Am I finding my way back to Christ? Maybe through Ambedkarism, Hard Conversations™ & yearning 80s synth pop? I think I’m supposed to be healthy now, face washed and trauma-adapted, free of shame, & fear; hallelujah! I’m supposed to cool down and mellow—Christ of abundance, the sacrament of plenty. Exit, peace pursued by therapy.

My favourite prophet, Isaiah, saw the coming of Christ, foretelling[10] that he would be “despised and rejected of men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief: and we hid as it were our faces from him; he was despised, and we esteemed him not”. And I think, me too, brother.

When I was younger, I was smitten of God and afflicted. It used to burn in me – pillar of flame, Old Testament-style. I knew it was a mystery from how it roiled in my body.

The body, the blood, the artefact of the body. The visions, the faith, the cornerstone, the stumbling block. The queer ecstasy, never the end, the betrayal; the beginning, the miracles, the cliffs, the wine, the waves. The vinegar, the denial, the dark rolling over the hill of Golgotha, the passion. Jesus’ death split the veil between God and man in two, and most of us in this country, across this subcontinent, belong to the tradition of his scattered, persecuted church. No better friend for the politically inconvenient; no better brother to the societally damned.

I’m a little older now. There’s so much about my community/ies and my faith that I still don’t know. The darkness facing us seems all-consuming, and these days I think (blasphemously maybe) the only real happy ending is Not Over Yet. I guess I’m just not as fanatical as I used to be.

But the passion still lies close to the surface. Under my skin, in the sense-memories of embraces from people who aren’t here anymore. I’m only still waking up, muzzy from dreaming, but every day with more clarity and anger like a dowsing rod. I know the weight of the God who tests me still. I think everyone forgets that the last book of the Bible, after all, is Revelations.

Footnotes:

[1] Hritik told me to read this back in 2019, telling me that “Babasaheb had great regard for Christian missionary work” and asked me to share what I thought. This whole essay, in a way, is my response to her kindness and friendship.

[2] Anyway, according to Rupa Viswanath’s The Pariah Problem, Christianity was considered a “pariah religion” in nineteenth-century Tamil Nadu, which I’m sure also plays a part in this provision.

[3] I hated the exclusive apolitical (low-key casteist) Christianity of my childhood church and the terrorising moralising (sexist) Christianity of my school, and I could not find even a fingernail hold in the oversimplified feel-good (borderline racist) culture of the local congregation at university.

[4] Basically, symbols, stories, references and prophecies of Jesus, that are scattered and reinforced throughout the Old Testament.

[5] I saw Rajyashri Goody’s installation ‘Is the Water Chavdar’ this August. Standing in front of 10k ceramic stupas, I felt such a thrum of familiarity.

[6] Originally, Peter’s name was Simon. Jesus gave him the title of Cephas (from Aramaic Kepa [“Rock”]; hence Peter, from Petros, a Greek translation of Kepa). The exact occasion of when he was given is title is debated but its relatively sure that he was given this personal title, and with it a mandate and position, upon whom the “community of the faithful [to Jesus]” would be built.

[7] Prescription Against Heretics, Tertullian (c. 155 – c. 240)

[8] According to Seeking Begumpura, “there was also an implicit acceptance in Ambedkar that Christianity and Islam were alien, something made explicit when he said once in a discussion with another Anti-Brahman convert that choosing Buddhism was like moving to a different room in a house, whereas the choosing of Christianity would be moving to a different house (cited in Aloysius, introduction to Dharmateertha 2004, iv-vi). Thus, in many ways, the choosing of a Christian identity – following Christ, the acceptance of baptism – however, defined, appeared the most radical break from Hindu nationalism.”

[9] It goes on “Women received their dead raised to life again: and others were tortured, not accepting deliverance; that they might obtain a better resurrection: And others had trial of cruel mockings and scourgings, yea, moreover of bonds and imprisonment: They were stoned, they were sawn asunder, were tempted, were slain with the sword: they wandered about in sheepskins and goatskins; being destitute, afflicted, tormented; (Of whom the world was not worthy:) they wandered in deserts, and in mountains, and in dens and caves of the earth.”

[10] Isaiah 53:3

Audio Credits:

Parai drums: Parai Instrument Sound Effect (Royalty free)

A crowd of Hindus burnt down a church – https://freesound.org/s/541014/ – This work is licensed under the Noncommercial 4.0 License.

Aime Cesaire- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FkTDayrLZq4

But I’m Talking About Faith – https://freesound.org/s/634813/ – This work is licensed under the Noncommercial 4.0 License.

Peter the rash: Gregorian Chants Vs. Modern Trap/Rap Beats [prod. Ryz]