Maveli is an important symbol of the rejection of brahmanism by the avarna peoples, and is a marker of the dissonance that underlies Hindu myths.

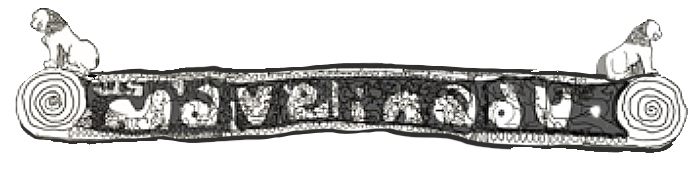

Illustration by Shrujana N Shridhar

Maveli or Mahabali or Bali is a mythical figure and a folk hero across Maharashtra and Kerala. He is mentioned as the “King of Asuras” in several Hindu scriptures, from the Vedas to the Puranas. Once the ruler of the three realms (the sky, the earth and the netherworld), he was tricked and defeated by Vamana, an avatar of Vishnu.

Maveli is an important symbol of the rejection of brahmanism by the avarna peoples of Kerala, and is a clear marker of the deep dissonance that underlies Hindu myths. The Bali myth remains alive to this day in multiple parts of the country, revived many times over as a symbol of cultural resistance by anti-caste leaders like Jotiba Phule and Sahodaran Ayyappan. We must remember Maveli, his story and its vital role in the search for our truth and our history.

The Story:

The great-grandson of asura Hiranyakashipu, Maveli was just and generous, and a deeply loved leader. In the first myth, Maveli’s renown and invincibility made the gods jealous, who then hatched a plan to defeat the asuras. They requested Maveli to help them retrieve Indra’s treasure from the celestial ocean that it had fallen into, all the while trying to create the nectar of immortality to defeat the asuras in war. Only Maveli was skilled enough to churn the entire ocean, and in a bid to achieve peace between the two clans, he agreed.

The trickery of the gods was soon revealed, and a war broke out between the gods and asuras – which the asuras won. The story goes that this ushered in an era of peace in the land, remembered in Bahujan folk memory as one marked by equality between people, and no discrimination or malfeasance of any kind. This was Mavelinadu, the land of Maveli. He was of the land and he honoured it, honoured its people and rejected the varnashrama dharma.

In brahmanic tellings of the tale, the rule of asuras is depicted as a dark and evil time, one that outright rejects vedic and brahmanical teachings. As Mahabali grew stronger and more popular, the gods created yet another plan to unseat him. They sent Vishnu in the form of Vamana, a brahmin who asked Bali for a piece of land the size of three paces. Mahabali was renowned for his generosity, and granted the wish immediately, thinking it a very humble request. But immediately, Vamana grew to “cosmic size”, and placed one foot on the earth and the other on the sky. Not one to go back on his word, Bali accepted defeat and Vamana placed his foot on his head, pushing Bali into the underworld along with the other asuras.

The people of Kerala rejected Vamana, and pleaded to their ruler to visit them every year. The return of Maveli to his land every year is Thiruvonam or Onam, a harvest festival celebrated in remembrance of an egalitarian past, and dream of a similar future.

Myths need to be understood in their context, and are often a reflection of their time – especially in the way they are framed, and how certain groups become antagonists in stories. These myths become propaganda pushed onto people by those trying to establish a hegemony. The victory of Vamana over Maveli signals the arrival of brahmanism and varnashrama in Kerala, and its subsequent erasure of a shramanic past.

“It is obvious that Vamana’s triumph over Bali signifies the defeat of Buddhism by Vaishnavite Brahmanism in the early Middle Ages throughout India. The thousand names or “Sahasra Nama” of Vishnu and Shiva also testify to the conquest and erasure of numerous Jain and Buddhist shrines and their localized deities by proponents of Brahmanism, using their two chief masks, the popularized Bhakti cults of Vaishnavism and Saivism. That is how they conquered the whole of India in the Middle Ages, annihilating the rationalist scepticism of Buddhism and its anti-caste, and therefore, anti-brahmanical, critical egalitarianism.”

It was a man named Sahodaran Ayyappan – a disciple of Narayana Guru, an Ezhava poet and anti-caste activist, who revived the story of Maveli in Kerala. He penned a version of the Onapaattu (song of Onam) that is a critique of the brahmanism that has burgeoned in Kerala since the 8th century CE. He calls for a return to the time of Mavelinadu, before the feudal Hindu system infiltrated the land and created notions of purity and pollution.

To people belonging to marginalised castes in Kerala, especially avarna people, Mahabali remains a symbol of a past that was untainted by the disease of brahmanism. There have been a number of attempts to sanitise this story of its revolutionary importance, and to appropriate Onam into a Hindu festival, even rebrand it as “Vamana Jayanti”. This is an insult to the cultural legacy of Maveli, and we must reclaim this story, passed on to us through generations of oral tradition. We assert that Maveli is a symbol of our historical struggle against caste, and an egalitarian shramana tradition that lingers in our memory.

“വാമനാദര്ശം വെടിഞ്ഞിടേണം

മാബലിവാഴ്ച വരുത്തിടേണം”

Vamanadarsam vedinjidenam

Mahabalivazhcha varuthidenam.

“Let us leave the ideology of Vamana,

And regain the just rule of Maveli.”

इडा पिडा टळो, बळीचे राज्य येऊ दे

“Ida pida talo, Balicha rajya yevo”.

Let troubles and sorrows go,

and the kingdom of Bali come.

Sources:

Antigod’s Own Country by A.V Saktidharan

Essays on the History and Society of Kerala by K.N Panikkar

A Social History of India by S.N Sadasivan

Slavery by Jotiba Phule

https://www.forwardpress.in/2016/01/violent-brahmanization-of-mahabalis-own-country/